CSI: Dollhouse

The making of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death dioramas

Dolls + miniature crime scenes = the most effective method of teaching homicide investigation! Who knew?!

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death are a special collection of dioramas. Built in the 1940s by a remarkable woman named Captain Frances Glessner Lee, they’re still used as valuable teaching tools today (despite being nearly 80 years old). You can read her extraordinary story here in my dissection of the book 18 Tiny Deaths. This post, however, is devoted to the detailed construction of the Nutshells.

“The investigator must bear in mind that he has a twofold responsibility—to clear the innocent as well as to expose the guilty. He is seeking only facts—the Truth in a Nutshell.”

Let’s Back Up And Set The (crime) Scene

Crime scene investigation was a nearly nonexistent science in the 1940s, and Captain Lee hoped to revolutionize the field. First, she established the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University. Then she began an innovative new project: building miniature crime scenes.

While her new department sought to train medical examiners and forensic pathologists, her dioramas were built to train law enforcement. It was a bold move, asking cops to “play” with dolls.

Until then, police officers and detectives routinely bungled crime scene investigations. They weren’t trained on how to look for and collect evidence. They were ignorant about postmortem changes in bodies and blunt or sharp force injuries. Unexpected and unusual deaths were beyond their meager skill set.

Captain Lee aimed to remedy their lack of training by developing a one-week seminar covering this specialized knowledge.

Conundrum

How do you teach someone how to observe? How do you do it without leading them? How can you arrange for a live crime scene for your students to study? Captain Lee dismissed photographs and films as being too two dimensional and leading. Live crime scenes were impossible to prearrange, and attendees couldn’t be given sensitive information about pending cases.

She quickly realized that the perfect solution was miniature models of crime scenes. They could be inspected at leisure and present a wide variety of circumstances. The solutions could be ambiguous, forcing students to observe and ponder minute details. They’d also have to discover the clues on their own rather than be directed to key points like they would have been with photos or film.

Crafty Solution

So, why not try 3-D miniatures? Captain Lee had experience crafting small, detailed models. As a wealthy young woman, she was taught a variety of artistic skills. Besides learning about literature, art, music, science, languages, dance, and horseback riding, she was also adept at sewing, knitting, crochet, and needlepoint.

In 1912 (age 34), she took on her first major miniature project. Since the Glessner family were ardent and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, musicians often performed privately for them at home. Captain Lee’s mother (also named Frances) joked about wishing she could have the orchestra playing there every day. Frances Jr. decided to hand-make a model orchestra for her mother’s birthday.

The real Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra had 90 members. Captain Lee dutifully recreated them ALL, including the conductor, in the standard dollhouse scale of 1:12 (one inch = one foot). In order to personalize each musician, Captain Lee attended rehearsals and sketched details like hairlines, facial hair, and eyebrows. She used substances like porcelain, mucilage, and plaster of Paris to customize her dolls, painting them with color matched enamel.

The model Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Each figure wore tiny formal evening dress: white shirts, pearl buttons, a black single-breasted waistcoat, matching evening coat, and detachable paper wing collars. Captain Lee sewed the garments herself, including the conductor’s fancy swallowtail evening coat. She even attached miniscule fabric carnations (1/6” across) to their lapels, duplicating the real carnation boutonnieres her mother always sent to the musicians before performances.

Besides the human figures, Captain Lee needed set dressings. She hired a carpenter to build an 8-foot-long tiered platform and purchased 90 wooden dollhouse chairs. They cobbled together the instruments with a combination of store-bought miniatures and others handmade using wooden candy boxes and other household items. Each was of the exact proper scale and looked realistic. She added six mini potted palms behind the orchestra and two vases of pink roses next to the conductor.

The conductor’s real-life counterpart was so grateful for years of financial support from the Glessners that he contributed his own skills to the project. Using a magnifying glass and postage stamp sized paper, he wrote accurate sheet music for each performer’s music stand. It was a score from Mother’s favorite piece, The Drum Major of Schneider’s Band.

When the miniature orchestra was presented to Mother on her 65th birthday in 1913, it was very well received. Father commented, “Nothing could be more complete or perfectly done, or more interesting.” A couple of weeks later, the real orchestra was invited to view the model. It fascinated them, and they returned again and again to inspect their miniature selves.

The model remained in a display case at the Glessner home for many years before being donated to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Practice Makes Perfect

Captain Lee made another set of musicians modeled on the Flonzaley Quartet. They were basically the hot new boy band of that era. With her practiced skills and improved techniques, the miniatures were even more detailed than the orchestra.

The real Flonzaley Quartet

Each model showed distinct personal characteristics and accessories like pinstriped trousers, bow ties, and a gold watch chain. She inserted wire frames so the dolls would sit and hold their instruments properly. Their heads were made from fish glue and plaster of Paris, covered with cotton fiber and painted to match each musician’s hair.

The model Flonzaley Quartet

After two years of secretly working on the four dolls, the Glessner family invited the quartet to dine at their home. The unsuspecting guests enjoyed their meal around a fancy floral centerpiece. After dinner, the centerpiece was removed with a flourish, revealing the handmade quartet. The musicians were stunned into silence, then suddenly burst out into spirited conversation. They were delighted.

On To The Morbid Stuff

Given Captain Lee’s experience with crafting miniatures in exquisite detail, it was natural that she’d gravitate to them to solve her crime scene conundrum. Model crime scenes were the perfect teaching tool for her homicide investigation training seminars. She began by commissioning her carpenter to build an 18”x18” box and advised him to bring his smallest and finest tools (they later used dental, jewelry, and watchmaking tools).

Here are some of the astonishing construction details for The Barn:

Built in the 1:12 or 1”:1’ scale, meaning a 6’ tall human would be a 6” tall doll.

Based on a fictionalized version of an actual crime scene (a man was hanged under unusual circumstances; known for repeatedly manipulating his wife with non-serious suicide attempts, he accidentally completed the suicide after his stand broke underfoot).

The Barn measured 27” tall from base to tiny weathervane, and about 2’ per side.

Using aged salvaged wood from a real barn on Captain Lee’s property, the carpenter fashioned it into planks using this process: he carefully removed the bleached and worn outer surface of the wood with a saw, making sheets of wood 1/12” thick. He cut the sheets into ½” strips and glued them together into 2x6” planks with aged wood on both sides.

The interior of the barn was filled with straw and an assortment of tiny farm tools, including a scythe made of an oyster knife. The saw was razor sharp and could draw blood.

The ox yoke was painted a delicate blue, then attached to a string and dragged through dirt to created a worn effect.

The back window showed a painted view of Captain Lee’s local railroad station.

The ceiling was covered with fake cobwebs and dust. A real cobweb had to be removed because the scale was incorrect.

The accidental suicide victim dangled from a hoist with a flimsy broken wooden crate underneath.

Captain Lee even included “Easter eggs” like a horseshoe nailed above the barn door (open side down, in the unlucky fashion) and a 1” tall hornets’ nest concealed beneath the eaves.

The attention to fine detail seems excessive, but Captain Lee was a perfectionist.

She maintained extremely high standards, demanding the very best for her training seminars. Refusing to use anything that would ruin the illusion, she even consulted with a forestry professor at Yale about which varieties of wood had a fine enough grain to be plausible in her 1:12 scale.

She experimented with textiles. Her material requirements were particular: must be thin and pliable without being transparent, must be capable of taking a crease, must not ravel easily, must drape properly, must get wet without damage, and the color and pattern must be correct.

Sometimes, a fabric would meet all of her restrictions and yet be unusable because the actual texture was out of scale. The lace work, doilies, and stockings were all hand knitted, using small straight pins as knitting needles.

Fun fact: the dolls all wore underwear beneath their clothing. You know… because anything less would have been indecent.

The Nutshells intentionally represented lower middle-class homes and poverty-stricken tenements, rather than perfectly furnished mansions. Captain Lee insisted that the homes be realistic, looking lived in and shabbily cluttered. The victims were more often than not women, and domestic violence was apparent.

Captain Lee sought to draw attention to marginalized crimes and train her predominantly male detective students to give every death a fully attentive investigation.

The commitment to realism meant that store-bought dollhouse furnishings were often unacceptable. The décor was too fine or period specific. Captain Lee’s carpenter handmade a variety of plain wardrobes, bedside tables, and chairs. Another hurdle that hampered construction was World War II. Materials were scarce or rationed. Tools and electrical motors (to make small scale tools) had to be applied for.

Captain Lee used her wealth and connections to find small treasures, like some Lucite rejected by the Navy. She overpaid for a scale model car, which was difficult to find after toy factories suspended production during the war (she wanted a car wreck diorama in which the female driver had been murdered and then staged as a crash).

Again, the details in the dollhouse production were staggering. Here are some more highlights:

The carpenter had to make his own nails, since the correct scale nails weren’t commercially available.

He also had to make correctly proportioned door hinges by grinding ½” hinges down to ¼”.

Glass from real picture frames was repurposed as openable windows.

An artist painted backdrop murals and a 2”x1” oil painting (of Captain Lee’s cottage) to hang over a fireplace.

A solid gold working hand mixer from a charm bracelet was purchased and painted gray.

Pantries contained accurately labeled brand name products, including tiny labels for whiskey bottles.

There’s graffiti on the jail cell’s wall.

Some books opened and had printed pages inside.

The saloon had a stamp sized poster advertising a boxing match.

Tiny extras were scattered all about: toy blocks, cigarette butts, mousetraps, and spent shells.

A divan had real springs and a mattress.

There were tiny working light fixtures illuminating the models from within.

The pillow next to a dead woman showed a lipstick stain on the underside.

Properly dated calendars hung on the wall, including the months following the death.

Most of the furniture and small objects worked: doors and dressers opened, stove lids lifted, corks came out of bottles, the grindstone was real and turned, halters and belt buckles worked.

Red nail polish was used to simulate blood spatter on walls, puddles of blood, and bloody footprints.

Linoleum was rubbed with a fabric wrapped finger to create authentic worn patches.

Besides the perfect crime scene settings, Captain Lee created tiny corpses to populate them. Unsurprisingly, miniature dead bodies were not available at the doll supply store. Dolls were typically made into fixed, standing positions, often on bases. It clearly wasn’t an option to merely tip them over.

Instead, Lee made her own, using leftover porcelain heads from her previous projects. She finished them with wigs or painted plaster hair, and gave their bodies the proper heft and appearance by filling them with sawdust, cotton, sand, or lead shot. Stiff wires inside the limbs held specific positions and depicted rigor mortis.

Attending autopsies gave Captain Lee the knowledge to ensure accuracy in painting skin discolorations like lividity, carbon monoxide poisoning, decomposition, and signs of violence.

This Sounds Expensive

It’s a good thing that Captain Lee was phenomenally wealthy. She didn’t keep itemized accounting on her Nutshell expenditures, but some estimates say she spent a range of $3000-$6000 in materials and labor per diorama. Adjusted for inflation, that represents approximately $45,000-$90,000 per model in today’s currency, and the total for 20 dioramas = $900,000-$1.8 million.

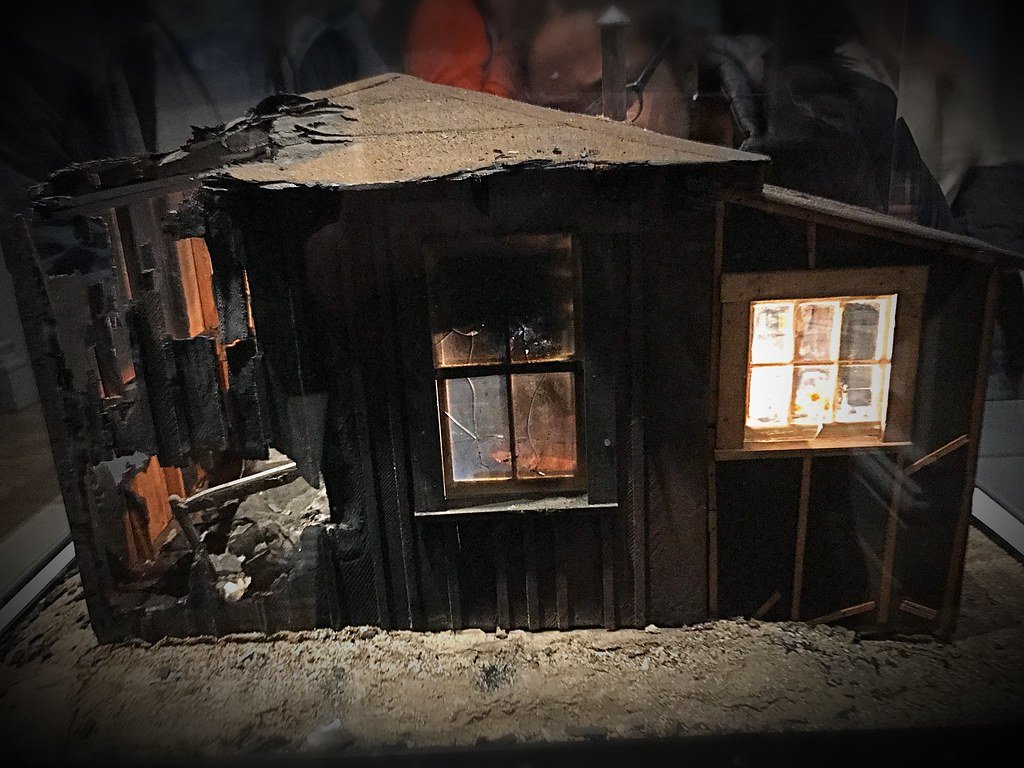

Remarkably, the significant investment didn’t stop Captain Lee from taking a blowtorch to one of her Nutshells. In “Burned Cabin,” she created a rural two-room cabin with a patched tar paper roof, a comfy chair near a wood stove, an iron framed bed, and a simple kitchen stocked with food and a kerosene stove. Despite spending thousands of dollars and countless painstaking hours creating this miniature work of art, she deliberately burned most of one corner of the cabin, until the bed began to fall through the floor.

Two Rooms

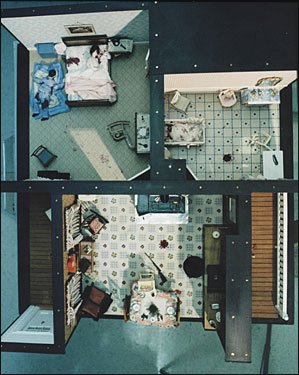

Out of the original 20 Nutshells, one has been lost to time. “Two Rooms” was damaged or destroyed in the 1960s. It was apparently one of the most elaborate models, comprising two nearly identical rooms, side by side. This diorama showed how a misguided police officer could inadvertently alter his crime scene and render it useless. The room on the left depicted the moment after a man was shot and killed. The room on the right showed the same scene, after the officer “helpfully” moved the body onto the couch and allowed the widow to sweep up shattered debris.

While the two rooms appear the same, there are over 30 differences for the finding. Some of the fine detail in this diorama included an officer holding a pencil made from a toothpick containing an actual piece of lead, a notebook with tiny indecipherable notes, and a working whistle hanging from the officer’s neck on a very fine platinum chain.

The Remaining Nutshells

Each Nutshell is displayed with some background information that sets the scene. Here is the original text. Feel free to skim or move along to the photo gallery and conclusion.

-

Reported Tuesday, December 24, 1946. Jessie Comptom found dead in her house by Harry Frasier, a milk delivery man. Mr. Frasier gave the following statement:

On the morning of Tuesday, December 24, about 6:00 a.m., he stopped at Miss Comptom's kitchen door to deliver the milk. The weather was very cold and he was surprised to find the door open. He put his head inside and called, but received no answer, so he then went part way up the attic stairs and saw Miss Comptom's body hanging there, so he went downstairs and telephoned the police.

Policeman John T. Adams received the telephone call at 6:43 a.m. Tuesday morning, December 24, and went at once to Miss Comptom's house. The snow on the path to the kitchen door was somewhat trampled and no distinct footprints could be recognized. There were unwashed dishes for one person on the kitchen table. The house downstairs was neat. The bed was made and undisturbed. However, he found the attic as represented in the model.

-

Reported Saturday, July 15, 1939. Eben Wallace, local farmer, found dead by his wife. Mrs. Wallace gave the following statement:

Mr. Wallace was hard to get along with. When things didn't go the way he wanted, he would go out to the barn, threatening suicide. Mr. Wallace would stand up on a bucket and put a noose around his neck, but she would always manage to persuade him not to do it. On the afternoon of July 14, about 4:00 p.m., they had a dispute. Mr. Wallace made his usual threats, but she didn't follow him to the barn right away. When she did go to the barn, she found the premises as represented in the model.

The bucket usually stood in the corner just inside the barn door, but yesterday she had used it and left it out by the pump. The rope was always kept fastened to the beam just the way it was found--it was part of the regular barn hoist.

-

Reported Wednesday, November 3, 1943. Charles Logan, box factory employee, found dead by his wife, Caroline Logan. Mrs. Logan gave the following statement:

On Tuesday night, November 2, she was alone in the house when Charles came home about midnight. He had been drinking and was in a quarrelsome mood. They had an argument, but she was finally able to persuade him to go upstairs to bed. She waited downstairs for him to go to sleep before she also went to bed. After about an hour, she heard him moving around and shortly thereafter heard a shot. She ran upstairs and found the scene as illustrated in the model.

-

Reported Sunday, August 15, 1943. Daniel Perkins missing and presumed dead. Phillip Perkins, Daniel Perkins' nephew, gave the following statement:

On Saturday evening, August 14, he came to spend the night with his uncle, as he frequently did. In the middle of the night, he was wakened by the smell of smoke and ran outside to find the house on fire and the fire engines arriving. He said he had been very confused and could not remember any other details.

Joseph McCarthy, driver of Fire Engine #6, gave the following statement:

The call to the fire was received at 1:30 a.m., Sunday, August 15. Upon arrival of the fire engine, the fire was quickly extinguished before the building was completely destroyed. He noticed Phillip Perkins, fully clothed, wandering around near the house.

The model represents the premises after the fire was extinguished and before the investigation was started.

-

Reported by Desk Sergeant Moriarty of Central City Police, as he recalled it. Maggie Wilson found dead by Lizzie Miller. Miss Miller gave the following statement:

Miss Miller roomed in the same house as Maggie Wilson but knew her only as they met in the hall. She thought Maggie was subject to "fits" (seizures). A couple of male friends came to see Maggie regularly. On Sunday night in early November 1896, the men were there and there was a good deal of drinking going on. Sometime after they left, Lizzie heard the water still running in the bathroom. Upon opening the door, she found the scene as set forth in the model.

-

Reported Monday, January 7, 1946. Hugh Patterson, Vice President of Suburban Bank, found dead in the garage by his wife, Sue Patterson. Mrs. Patterson gave the following statement:

Hugh went out alone in the car after dinner on Saturday, January 5. He often did this, especially lately, and would stay out very late. Sunday morning when he hadn't come home by breakfast, Mrs. Patterson went to the garage to see if the car was there. She looked in the left-hand door and saw Hugh hanging out of the car. She then telephones the local police station for help as she couldn't reach the doctor.

When the patrolman arrived, he went around to the back, broke the glass, climbed in the window and opened both doors. He left through the window so as not to disturb footprints in front. He found the garage full of gas fumes, the car's ignition turned on and the gas tank empty. Hugh had seemed troubled for some time and money hadn't been as plentiful as it once was. Some time ago he told her that he carried heavy life insurance, with the double indemnity clause for accident, in her favor, and about that time he deeded the house to her. He had begun to drink a good deal lately. The model shows the premises just after the patrolman left the garage by way of the window.

-

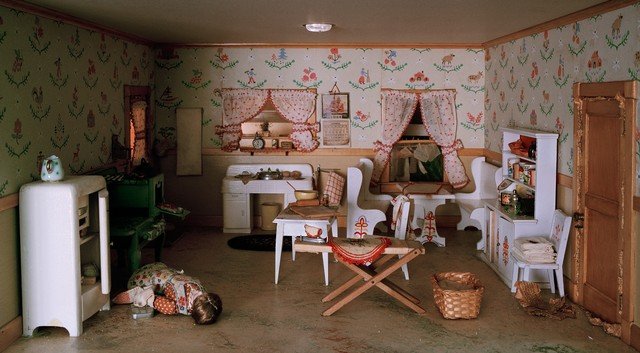

Reported April 12, 1944. Barbara Barnes, a housewife, was found dead by police who responded to a call from the husband of the victim, Fred Barnes. Mr. Barnes gave the following statement:

About 4:00 p.m., he had gone downtown on an errand for his wife. He returned about an hour and a half later and found the outside door to the kitchen locked. It was standing open when he left. Mr. Barnes attempted knocking and calling but got no answer. He tried the front door but it was also locked. He then went to the kitchen window which was closed and locked. He looked in and saw what appeared to be his wife lying on the floor. He then summoned the police. The model shows the premises just before the police forced open the kitchen door.

-

Reported Friday, May 22, 1941. Ruby Davis, housewife, found dead on the stairs by her husband, Reginald Davis. Mr. Davis gave the following statement:

He and his wife spent the previous evening, Thursday, May 21, quietly at home. His wife had gone upstairs to bed shortly before he had. This morning he awoke a little before 5:00 a.m. to find that his wife was not beside him in bed. After waiting a while, he got up to see where she was and found her dead body on the stairs. He at once called the family physician who, upon his arrival, immediately notified the police.

The model shows the premises just before the arrival of the family physician.

-

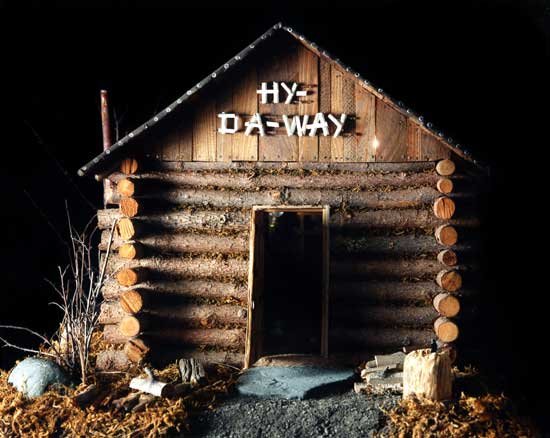

Reported Thursday, October 22, 1942. Arthur Roberts, local insurance salesman, found dead by police who responded to a call from a friend of the victim, Marian Chase. Mrs. Chase gave the following statement:

She met Arthur at the log cabin on Wednesday, October 21, about 5:15 p.m. They were in the habit of meeting there. Roberts was married and living with his wife. Mrs. Chase was also married but not living with her husband. Roberts told her at this meeting that the affair between them was ended. There was no quarrel. They were standing at the foot of the bunk. He turned towards the door, took a pack of cigarettes from his outside pocket, selected a cigarette, but dropped it. As he stooped over to pick it up, a shot was heard, he fell flat and a gun dropped beside him. Mrs. Chase picked up the gun but then replaced it. It did not belong to her. She then ran out of the door, jumped into her car and drove to summon the police.

The gun was identified as belonging to Arthur Roberts. Mrs. Close identified the handbag on the bunk as hers. A single bullet had passed entirely through Mr. Roberts' chest from front to back, and the powder around the entrance hole indicated that it had been fired at a fairly close range. The model shows the premises just after Mrs. Chase left and before her return with the police officer.

-

Reported Friday, August 23, 1946. Dorothy Dennison, high school student, found dead after reported missing by her mother, Mrs. James Dennison. Mrs. Dennison gave the following statement:

On Monday morning, August 19, about 11:00 a.m., Dorothy had walked downtown to buy some hamburger steak for dinner. She didn't have much money in her purse. When she failed to return in time for dinner, her mother telephoned a neighbor who stated that she had seen the girl walking towards the market, but had not seen her since. Mrs. Dennison also telephoned the market and the proprietor said he had sold Dorothy a pound of hamburger sometime before noon, but didn't notice which way she turned upon leaving the shop. By late afternoon, Mrs. Dennison, thoroughly alarmed, notified the police.

Lieutenant Peale's investigation report stated that on Monday afternoon, August 19, at 5:25 p.m., he received the call from Mrs. Dennison at Police Headquarters and at once took charge of the matter personally. The customary inquiries began and by Wednesday, August 21, a systematic search of all closed or unoccupied building in the vicinity was undertaken. It was not until Friday, August 23, 4:15 p.m. that he and Officer Patrick Sullivan entered the Parsonage and found the premises as represented in the model. Temperature during that week ranged between 86F and 92F with high humidity.

-

Reported Tuesday, March 31, 1942. Rose Fishman, widow, found dead by janitor Samuel Weiss. Mr. Weiss gave the following statement:

Several tenants complained of an odor, and on March 30, he began looking for the source of the odor. Mrs. Fishman didn't answer her bell when he rang it, and upon checking with other tenants he learned that she had not been seen recently. Therefore, he looked into her mailbox and saw that her mail had accumulated for several days. He entered Mrs. Fishman's apartment, found it in order but the odor was very strong. The bathroom door was closed. When he tried to open the door, he could only get it opened a little way and the odor was much stronger. He immediately went downstairs and climbed the fire escape to enter the bathroom through the window. He could not remember if he found the window open or closed. The model, however, shows the premises as he found them.

-

Reported Thursday, June 29, 1944. Marie Jones, prostitute, found dead by her landlady, Shirley Flanagan. Mrs. Flanagan gave the following statement:

On the morning of Thursday, June 29, she passed the open door or Marie's room and called out "hello." When she did not receive a response, she looked in and found the conditions as shown in the model. Jim Green, a boyfriend and client of Marie's, had come in with Marie the afternoon before. Mrs. Flanagan didn't know when he had left. As soon as she found Marie's body, she telephoned the police who later found Mr. Green and brought him in for questioning.

Mr. Green gave the following statement:

He met Marie on the sidewalk the afternoon of June 28, and walked with her to a nearby package store, where he bought two bottles of whiskey. They then went to her room where they sat smoking and drinking for some time. Marie, sitting in the big chair, got very drunk. Suddenly, without any warning, she grabbed his open jackknife, which he had used to cut the string around the package containing the bottles. She ran into the closet and shut the door. When he opened the door, he found her lying as represented by the model. He left the house immediately after that.

-

Frank Harris, dock laborer, found dead in a jail cell after found lying on the street by patrolman Dennis Mulcahy. Patrolman Mulcahy stated that on Saturday night, November 11, at half past eleven, he was walking his beat on Dock Street. He saw a man lying sprawled out on the sidewalk in front of Pat's Place, a saloon. The man was breathing and smelt strongly of liquor.

Mulcahy called the wagon, which took the man to Station 2, where he was locked up in a single cell. His union card bore the name of Frank Harris, address 27-1/2 Walter Street. He appeared to be very drunk. There were no marks of violence on him. On Sunday morning, November 12, at 7:00 a.m., when rounds were made in Station 2, Mr. Harris was found dead in his cell, as represented by the model.

-

Reported Saturday, October 25, 1947. Eugene Black, town drunkard, found dead. David Jackson, roomer in Black's house, gave the following statement:

Jackson has a large room over the woodshed. Coming home about 8:00 p.m. on Friday, October 24, he found Black lying on the couch in the sitting room, very drunk and apparently asleep. On the floor beside him was an uncorked bottle of whiskey and Gene's .22 rifle, which usually hung on two spikes on the woodshed wall. Knowing that Gene was dangerous when drunk, Jackson, deeming it unsafe for him to have a gun so handy, took the .22 and replaced it in its accustomed place, the shed. He then went up to his room, read a while and went to bed.

Winifred, Eugene Black's daughter, gave the following statement:

Her mother is a bedridden invalid who never comes downstairs. Winifred does all the work of the house and takes care of her mother. She also has a job as clerk at the local 5&10. This was necessary, as her father had no job and couldn't get one because of drink. On the evening of October 24, she and her father had finished supper and he had gone out again. She was upstairs with her mother with the radio going, tuned in to a Western with lots of shooting.

About 9:00 p.m. they turned off the radio and about a half hour later were startled to hear groans, apparently downstairs. Winnie went down and found her father on the couch, evidently dying. She at once telephoned Dr. Monroe, the family doctor, who also happened to be the deputy medical investigator. Upon his arrival, he made a brief and hasty examination of Black, who was dead by this time, and ordered the body taken to Coffin & Graves Funeral Parlor. At the same time, Dr. Monroe signed the death certificate, giving as cause of death, "acute alcoholism."

-

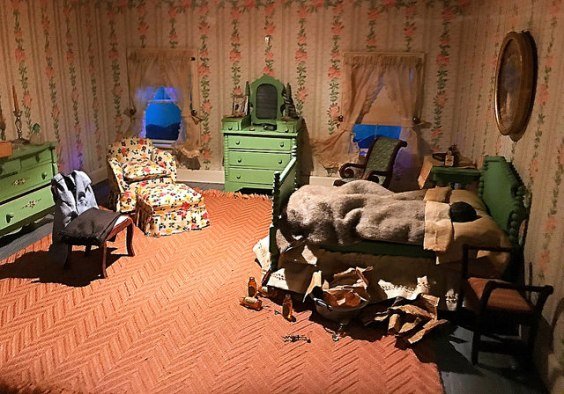

Reported Monday, April 29, 1940. Richard Harvey, ice-cream factory foreman, found dead by his mother, Mary Harvey. Mrs. Harvey gave the following statement:

On Saturday night, April 27, Richard came home for supper as usual and after supper went back to work. He always worked late Saturday nights to get ready for the Sunday trade. She didn't know when he came in as she had gone to bed early. Sunday morning, she let him sleep while she went to church and then, as usual, proceeded to her sister's for the day. When she returned home Sunday evening, Richard wasn't around so she opened his door and found the premises as represented by the model.

Richard was married about a year ago and brought his wife home to live. She is a nice girl and they were very happy. His wife was away now visiting her parents for a few days in another state. Richard was a good boy, but sometimes he had a little too much to drink, especially on Saturday nights. The dishpan belonged in the kitchen. She didn't know how it came to be in Richard's bedroom.

-

Reported Monday, November 1, 1937. Robert Judson, shoe factory foreman, his wife, Kate Judson, and their baby, Linda Mae Judson, found dead by neighbor Paul Abbott. Mr. Abbott gave the following statement:

Bob Judson and he drove to their work together, alternating cars. This was Abbott's week to drive. On Monday morning, November 1, he was late--about 7:35 a.m.--so, when blowing his horn didn't bring Judson out, Abbott went to the factory without him, believing Judson would come in his own car.

Sarah Abbott, Paul Abbott's wife, gave the following statement:

After Paul had left, she watched for Bob to come out. Finally, about 8:15 a.m., seeing no signs of activity at the Judson house, she went over to their porch and tried the front door, but it was locked. She knocked and called, but got no answer. She then went around to the kitchen porch, but that door was also locked. She looked through the glass, and then, aroused by the sight of the gun and blood, she ran home and notified the police.

The model shows the premises just before Mrs. Abbott went to the house. Dawn broke at 5:00 a.m.; sunrise at 6:17 a.m.; weather clear. No lights were on in the house. Both outside doors were locked on the inside.

-

Annie Morrison, housewife, found lying on the ground below a second story porch. Harry Morrison, husband of Annie, gave the following statement:

On Monday morning, April 5, at about 11:00 a.m., he was in the kitchen of the top story apartment where he and his wife lived. Mrs. Morrison had done the week's washing and was standing on a chair on the porch hanging it on the line to dry. Mr. Morrison heard a noise, went to see what it was, and found conditions as represented by the model. He had a job on the late shift but was up earlier than usual that day, as he hadn't worked the day before, which was Sunday.

Agnes Butler, a neighbor, gave the following statement:

She lived in the apartment below the Morrisons. She had bathed the baby on Monday morning, April 5, and put him in his carriage. She had done his wash and hung it out to dry. She was cleaning up the kitchen when she heard a crash, rushed out onto the porch and saw Mrs. Morrison lying on the ground below. The Morrisons quarreled a lot and Mr. Morrison didn't treat his wife very well. He drank and Mrs. Butler guessed he had lady friends. She heard the Morrisons quarreling that morning.

-

Reported Monday, June 4, 1949. An unknown woman found dead in a rooming house. Bessie Collins, landlady, gave the following statement:

She keeps a rooming house, and on Saturday, June 2, in the early afternoon, the deceased and a man rented this room until Monday morning, registering as Mr. and Mrs. John Smith. On Monday morning, June 4, the man left early--about 6:30 a.m. He paid for the room up to 6:00 p.m. and said not to disturb his wife, as she wanted to sleep late.

About 3:00 p.m. on Monday afternoon, Mrs. Collins told Stella Walsh, the maid, to try to get into the room to make it up. Just before 5:00 p.m., Stella told Mrs. Collins there was something wrong. She tried twice but couldn't wake the woman, so Mrs. Collins and Stella entered the room, the door of which was not locked, and found the woman was cold--evidently dead. They left the room without disturbing anything, closed and locked the door, taking the key with them, and notified the patrolman on the beat.

The model shows the conditions in the room as the two women found them. The case presents two problems: Who was this woman? The means of identification is clearly visible. What was the cause of her death? The medical examiner found the clue.

-

Ruby Jenks found dead in a woodman's shack she lived in with Homer Gregg and Carl Stebbins. On Tuesday, February 6, about 5:00 p.m., High Field Village Chief of Police Lawrence W. Farmer was notified by Dr. George Barbour of High Field Village that there was a dead woman in a lumberman's camp on Pine Grove Road. Medical investigator Chester W. Dombey, Deputy Sheriff Thomas Gorman, photographer Adam Stanhope, and Chief Farmer went over at once.

They found Mr. Gregg and Mr. Stebbins there, both very drunk, and the body of Ruby Jenks on the bed entirely covered up, including her head and face. Chief Farmer pulled the blanket down and Stanhope took a picture. Dr. Dombey made an examination of the body and ordered it removed to Coffin & Graves Funeral Parlor. Mr. Stebbins then lay down on the bed and photographer Stanhope took a picture of him and one of the outside of the shack.

At the funeral parlor, Dr. Combey again examined the body and found no marks of violence. Adam Stanhope took another picture here. The two men were questioned that night and again the next day. The model shows the premises as found by Dr. Barbour upon his arrival at 4:25 p.m. on Tuesday, February 6. Mr. Stebbins is lying on the bed--also Ruby. Mr. Gregg is seated on the chair. U.S. Weather Bureau Report: Weather clear; temperature 17F; sunset 5:03 p.m.

Photo Gallery of 19 Nutshells

So How Did They Use The Nutshells?

They installed the models in cabinets in a dark gallery for use during the twice-yearly homicide investigation seminars. Amidst the other curriculum (lectures and autopsy observations), they assigned each attendee two Nutshells to study. They were given 90 minutes per Nutshell as an exercise in observation, interpretation, evaluation, and reporting. Captain Lee stood nearby, ready to answer general questions but never revealing the closely guarded solutions.

The dioramas were not meant to be solved, as the cases lacked autopsy reports and questioning of witnesses. The skills gained were about avoiding snap judgements, not jumping to conclusions, or only collecting evidence that supported a hunch. After the observation period was complete, officers stood before the class and gave a verbal report. A discussion would follow, along with the point intended to be illustrated by each diorama.

Conservation and Repair

In 1961, several Nutshells suffered water damage after snow and ice leaked through the department’s roof. Mold grew on the leather and cloth materials. Captain Lee evaluated the damage and made the repairs in time for the Fall seminar. It would be the last seminar she attended before her death.

Harvard continued to hold the seminars until 1967. After that, they were moved to the state medical examiner's office in Baltimore, where they remain today for the benefit of countless new students. The Frances Glessner Lee Seminar in Homicide Investigation has been held continuously for half of a century and is the gold standard for all other training seminars of its kind.

Although the Nutshells have been largely concealed from the public, a rare opportunity presented itself in 2017. Seventy years of wear and tear had taken a toll on the models, plus they contained crumbling sheets of asbestos and ancient electrical wiring. Unsecure bits of evidence could potentially move and alter the interpretation. False clues could have been discovered as discoloration, cracks, and shrinkage gave the appearance of a broken or open window in a room that was meant to be sealed. The blood spatter (red nail polish) had faded, cracked, and discolored, which could affect the proper interpretation of patterns and drying time.

Experts from the Smithsonian Institution’s American Art Museum performed an extensive conservation. They painstakingly cleaned, repaired, and strengthened materials to slow or stop the effects of aging, heat, and UV light. Loose pieces of evidence were re-adhered, using as much original material as possible and only adding modern adhesive as necessary. The incandescent light fixtures were upgraded to custom designed computer-controlled LEDs inside tiny vintage-looking glass bulbs. They took care to match the original appearance and “temperature” of the lighting.

Click here for a short video about the conservation efforts.

Finally, A Public Viewing

Following the conservation, the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery hosted a special three-month exhibition (“Murder Is Her Hobby”) featuring the newly restored Nutshells. For the first time in 70 years, the public was invited to inspect the models. It was a massively popular event, attracting over 100,000 visitors. Would-be detectives were provided flashlights and encouraged to speculate. No solutions were given.

At the conclusion of the exhibition, the 18 pieces on loan to the museum (technically from Harvard Medical School, but via their custodian, the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner) were carefully transported back to Baltimore. The 19th “lost” Nutshell was on loan from the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, courtesy of the Bethlehem Heritage Society, and presumably returned to them.

Legacy

Some say that Captain Lee intentionally and subversively used womanly crafts to break into a man’s world. The juxtaposition of such a delicate, feminine art against such gruesome violence is certainly striking. Others assume she was a vocal feminist, given her inclusion of domestic abuse and sex workers. It’s difficult to say what Captain Lee believed. She shunned the spotlight, preferring her work to receive the attention instead. Unfortunately, little remains about the woman herself.

What will live on, however, is her contribution to the field of forensics and medicolegal investigation. Besides the innocent people cleared and the guilty people exposed as a result of proper investigation techniques, Captain Lee is responsible for an entire genre of modern entertainment. She carefully cultivated public opinion about her work by soliciting news articles, a Hollywood movie, and best-selling novels. These were the forerunners of shows like CSI and Quincy ME, which led to countless other reality shows, movies, books, and podcasts.

Who could have guessed where murder in a nutshell would lead?!

Sources and Links

Want more? Check out these books, websites, photos, and videos. Also, if you missed the companion piece I wrote about the Frances Glessner Lee book 18 Tiny Deaths, you can read my dissection here.

Book: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death by Corinne May Botz is a treasure trove of photographs, details, sketches, and a summary of Captain Lee’s story

Book: 18 Tiny Deaths by Bruce Goldfarb is a book about the coroner vs medical examiner system and Captain Lee’s contributions to the development of a new field of education

Exhibition: The Smithsonian’s website for the public Nutshell exhibit, with videos, images, and an interactive 360 virtual tour of 5 dioramas

Documentary: Of Dolls and Murder, narrated by John Waters

Article on repairs: “Crime Scene Conservation: Preserving the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death”

Article on crime against women: “These Bloody Dollhouse Scenes Reveal A Secret Truth About American Crime”

Article & short video on conservation: “Dollhouse death scenes, used as teaching tools in Baltimore, being refurbished for Smithsonian exhibit”

Website: an exhibition visitor’s photos and copies of the original text posted with each Nutshell

Video: 8 minute Vox segment “The dollhouses of death that changed forensic science”

Website: info and photos from Death in Diorama

Wikipedia: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death

Veteran funeral director, embalmer, and lifelong bookworm, Louise finally found her purpose: educating and entertaining strangers on the internet about dead bodies and funerals.

Her blog, Read In Peace, combines her passion to educate with fun and humor. She shares tips and useful information about death and funerals, along with lighthearted “dissections” of related books and movies.

Louise is currently working on her first book, a nonfiction guide called Embalming For Amateurs.