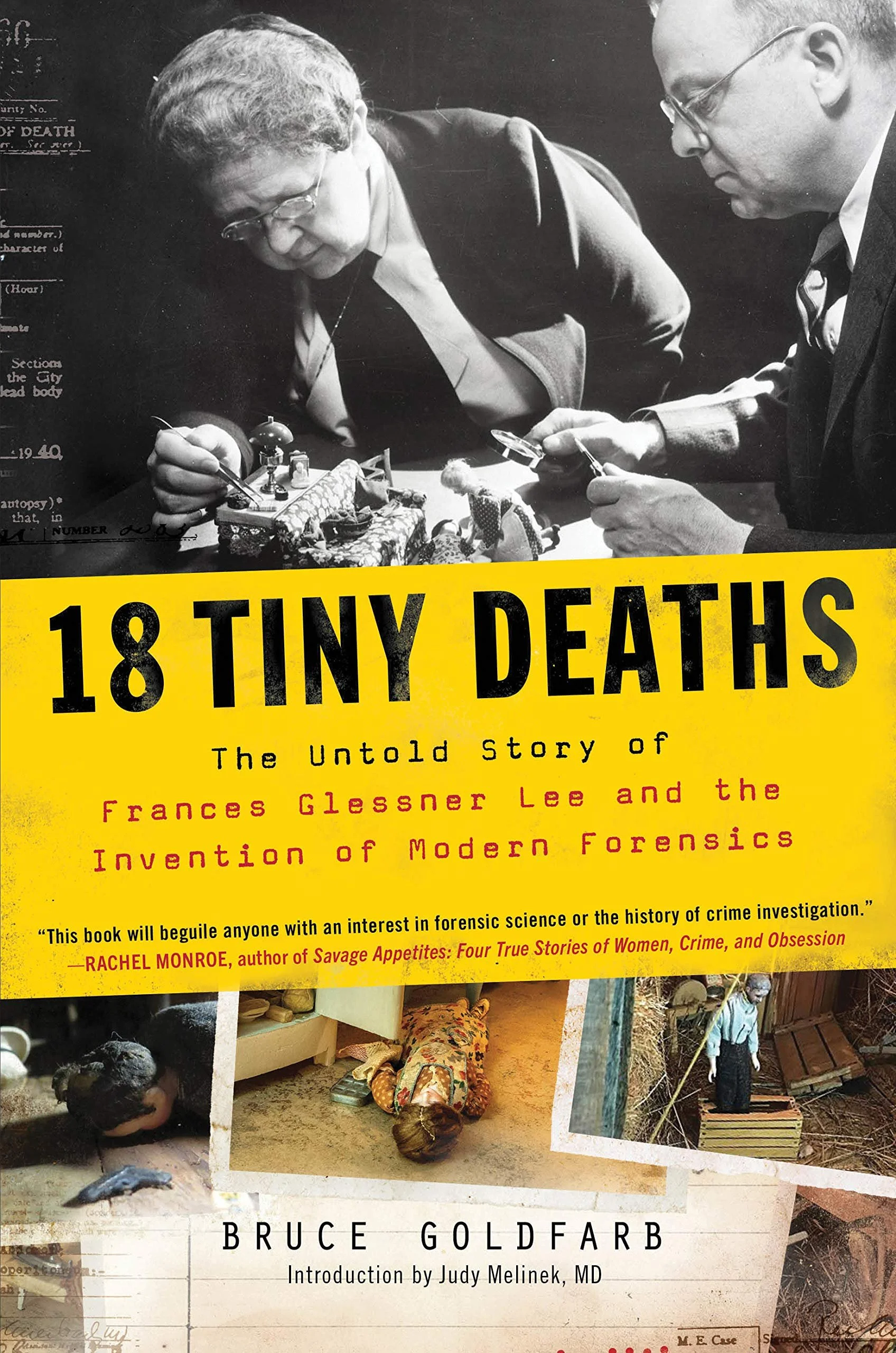

Book Dissection: 18 Tiny Deaths

The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics (using dollhouse murder scenes)

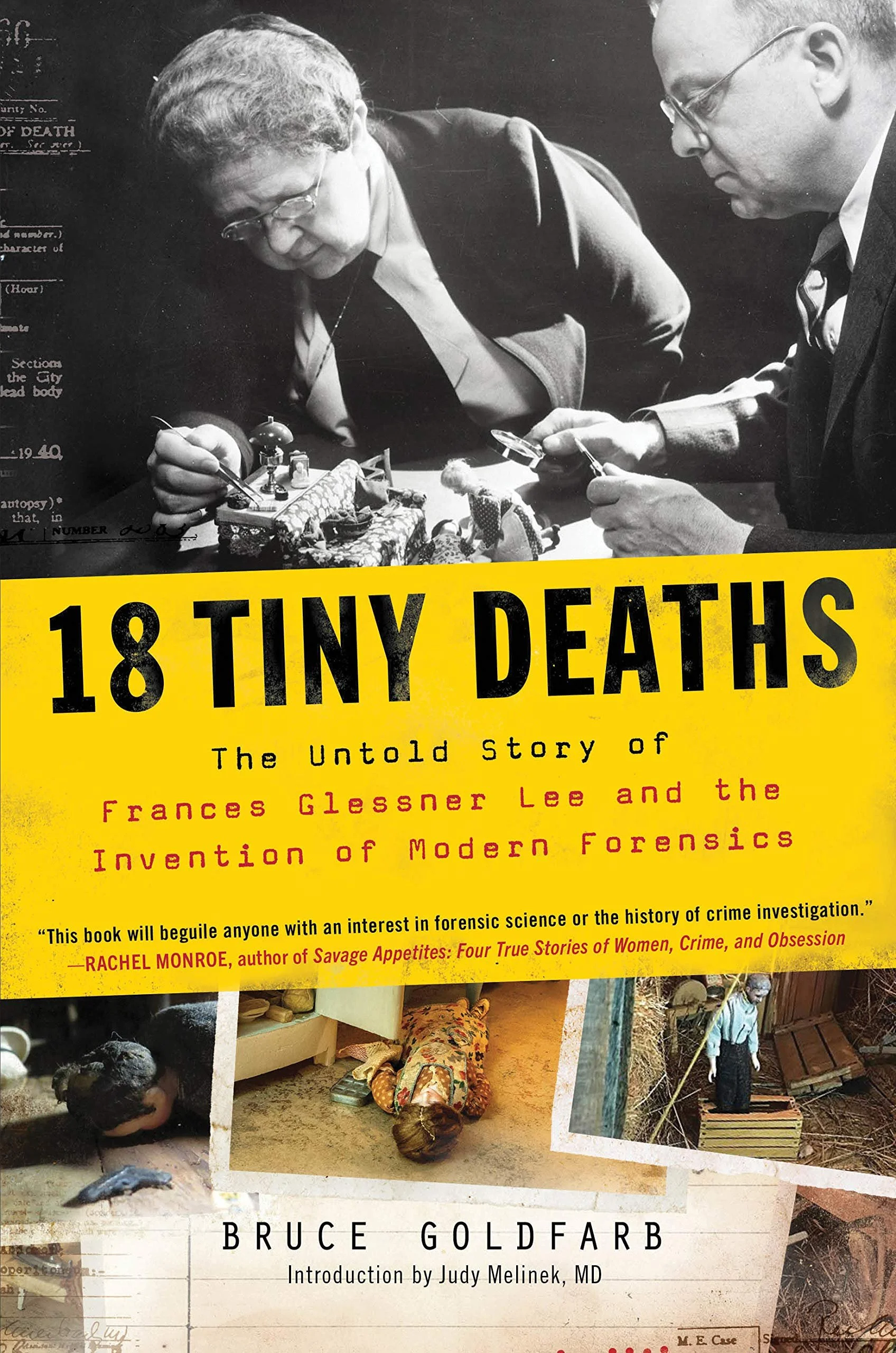

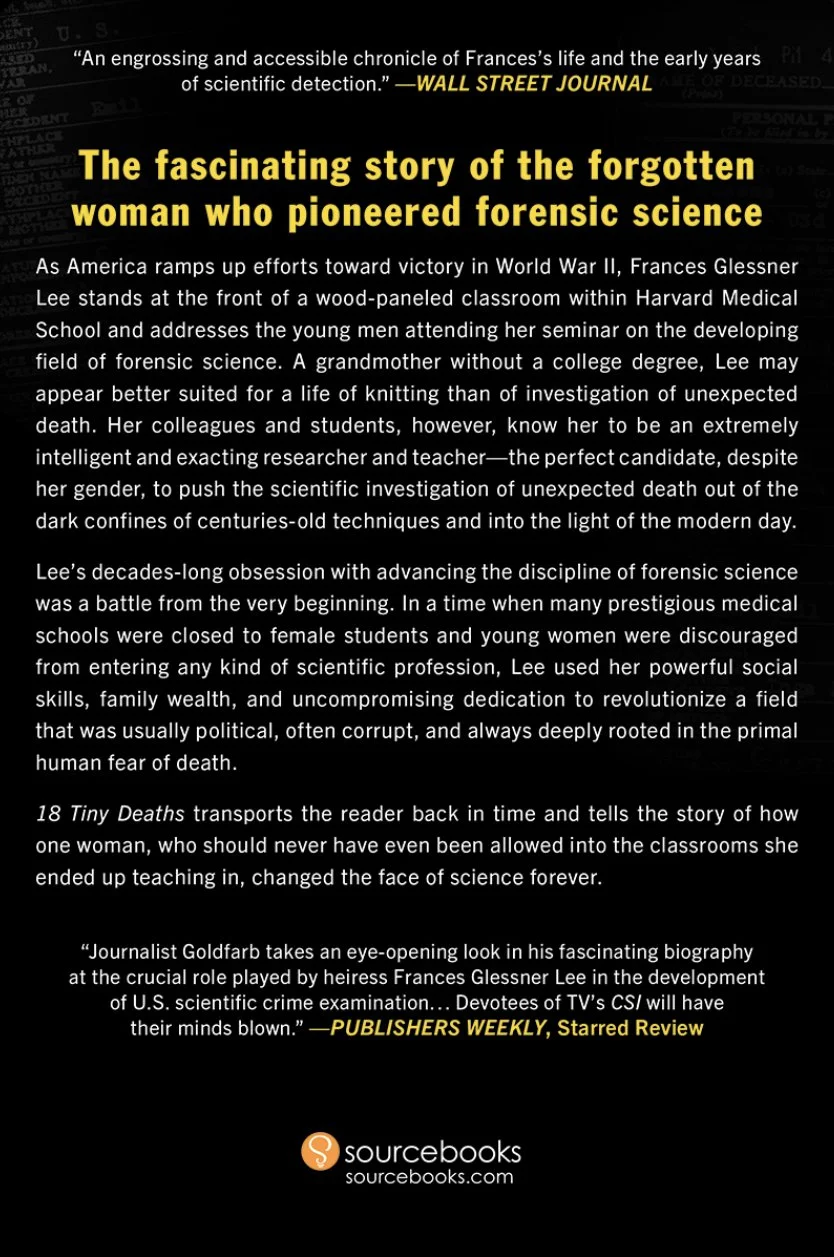

18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics

Author: Bruce Goldfarb

Published: 2020

Pages: 368

Genre: Nonfiction, True Crime, Biography

Amazon Link: 18 Tiny Deaths

TL; DR: The detailed history of Frances Glessner Lee (and other folks) who identified a need for medicolegal investigation and created a unique field of education to train police officers and medical examiners.

Highlight: 18 exquisitely handmade dollhouse sized murder scenes, known as the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

18 Tiny Deaths is a book worth reading, as long as you know a few things going into it. I expected it to be about Frances Glessner Lee’s life and the development of her brilliant crime scene dioramas. Well, it was, but… It was also a history of the antiquated coroner system, the switch to the medical examiner system, assorted disasters, lots of politics, and way too many details about random people in Lee’s life.

That doesn’t make it a terrible book, but prepare to learn every single fact the author discovered during his research. For the right reader, this book is fascinating. For everyone else, I’ll boil it down to its key points of interest (PostScript: my summary below turned out to be much longer than expected!)

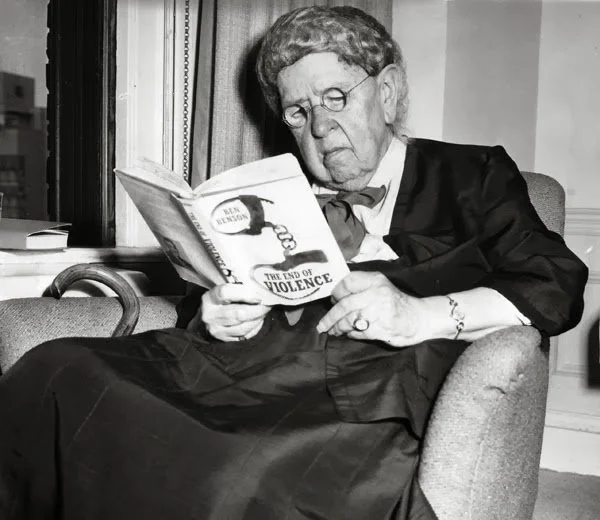

Who Was Frances Glessner Lee?

Image courtesy of Glessner House Museum

On the surface, she seemed like a rich, bossy grandma with too much time on her hands. In reality, she was driven to help others with her fortune and pursue interests well beyond what was available to women of her time.

Lee was born in 1878 to one of the wealthiest families in Chicago. She lived a life of luxury, enjoying a private education and a home atmosphere that valued cultural and intellectual self-improvement.

Though Lee wasn’t expected to work or seek higher education, she was extremely interested in science and medicine. Had she been born in a different era, she likely would have attended nursing or medical school.

Unfortunately, Lee’s family was loyal to Harvard University, which did not yet accept women. Medicine was “too indecent for their delicate sensibilities.”

Lee married in 1898 at age 19. The marriage produced three children, but ultimately her personality was incompatible with her husband’s. They came from vastly different families (basically The North vs The South), and he had different ideas about how a woman should act. Frances was not about to be cowed by the likes of him. She ditched Mr. Lee and lived her best life.

Through a fortuitous friendship and an off-chance remark about the beauty of internal organs, a one-of-a-kind idea bloomed and Lee changed the field of forensic science forever.

Influencing Events

Peppered throughout the book are quick mentions of massive disasters and infamous deaths. Some only loosely touch the main story, but they’re all individually fascinating and horrifying. Together, they illustrate the necessity of forensic investigation and well-trained medical examiners. Let’s take a brief look at these, and I’ll share links for further reading. These catastrophes led to significant changes in safety standards and mass fatality recovery and identification techniques.

-

The deadliest single building fire in US history; a Titanic-esque disaster involving a brand-new theater purported to be “absolutely fireproof.” Over 600 people died, most of them women and children. Many were burned beyond recognition. Lee’s family friends were involved, and her own brother assisted with the body recovery. Lee was deeply affected by the heartbreaking idea of losing a family member and not having an identifiable body to say goodbye to.

Read more about this ghastly catastrophe here and here (this one is a remarkable 389 page book, scanned and available for viewing online).

-

Summer Street Bridge Disaster: A streetcar crammed with 60 passengers plummeted off an open drawbridge and quickly sank into the 30’ deep channel. Divers recovered the 46 victims who were trapped inside and drowned. Lee’s good friend Dr Magrath was the medical examiner on scene.

-

A large storage tank burst, sending 2.3 million gallons of molasses flowing through the streets in a 25’ high wave. It rolled through at 35 mph, obliterating everything in its path and killing 21 people. It injured 150 people and also killed a dozen horses. Buildings were swept off their foundations. The victims struggled and died like flies on sticky fly-paper or were crushed by debris. The sweet smell of molasses lingered for decades.

-

The second deadliest single building fire in US history. The popular venue was packed to over double its legal capacity when a fire broke out in the basement lounge, killing 492. A single four-foot-wide staircase provided the only means of public escape, and the emergency exit at the top was locked. The main entrance to the nightclub was a revolving door, which quickly became jammed shut with piles of bodies.

A fireball exploded, igniting flammable décor and the methyl chloride gas in the air conditioning. Other exits were locked, boarded up, or couldn’t open inwards because of the crush of people forced against them. A local hospital received 300 burn victims, one every eleven seconds. Advances in burn treatment resulted from treating so many cases, and new laws passed mandating proper emergency exits.

-

The deadliest industrial accident in US history; 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on a ship exploded. A chain reaction of fires and other explosions ripped through the port, killing 581+ people. Fiery shrapnel, including a two-ton anchor, rained down over a mile from the blast. Over 5,000 people were injured. The seaport was destroyed, along with nearby businesses, 1100+ vehicles, 362 freight cars, and 500+ homes. Two small planes were blown from the sky.

So What Did Frances Glessner Lee Actually Do?

Well, she nearly single handedly created and funded a brand new department at Harvard University. Not bad for a woman without a college degree in a world dominated by men! To fully understand the magnitude of Lee’s accomplishments, we need to back up a step and learn what problem she was trying to solve.

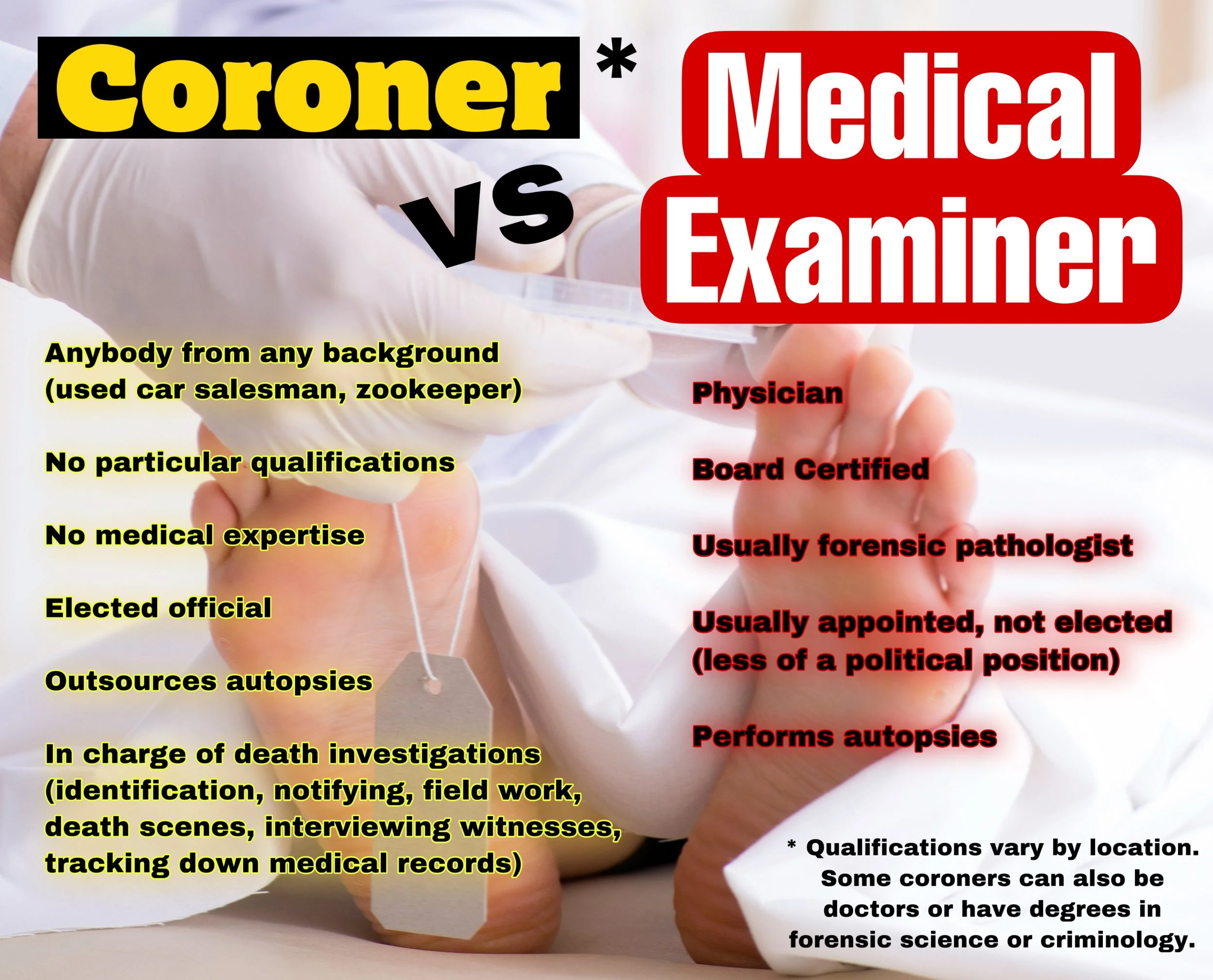

Coroners Vs Medical Examiners

Yes, there IS a difference! The book begins with a lengthy history of coroners before getting to Lee’s actual biography. I’ll condense it into the bare essentials, then get back to Lee’s contributions.

Here’s how the coroner system got started: way back in Medieval England, there was a job called “keeper of the pleas to the crown.” The title morphed into “crowner,” and then “coroner.” The coroner was tasked with collecting money owed to the monarchy. This was mostly taxes and fines, but also extended to seizing fancy fish for the king and investigating shipwrecks and treasure troves.

Another source of money was property forfeited by criminals. An executed murderer forfeited all of their land and possessions to the crown. They deemed suicide a crime against God, authority, or oneself, so those poor souls also forfeited their property to the crown.

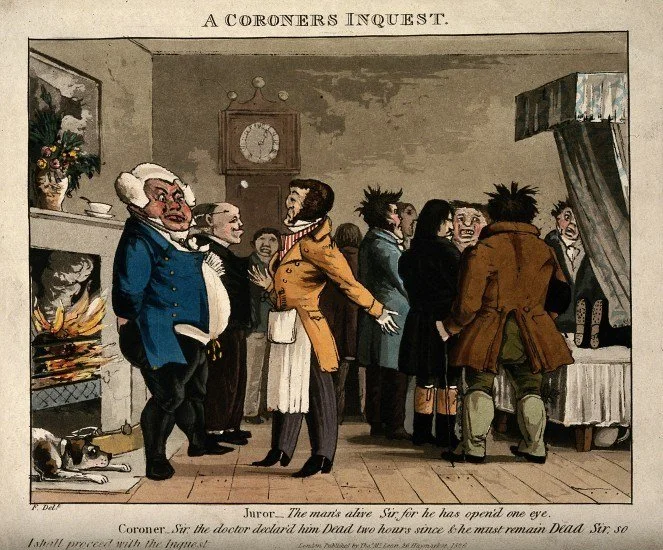

Since coroners could seize the property of criminals, it was in their best interest to investigate suspicious and unusual deaths for signs of wrongdoing. Their job was to determine what caused the death and who was responsible, despite having zero knowledge of medicine or criminal law. Instead of performing an autopsy, they’d hold an inquest.

A jury of 10-12 men (probably illiterate farmers) gathered to observe the body at the location of death. After looking at the body, they’d vote on what they thought had happened. If they decided it looked like murder, they had to name the killer. Then the coroner would charge and arrest the murderer and confiscate their property following the conviction and execution.

Fast forward from Medieval England to the new colonies of America in the 1600s. The European colonizers brought the coroner system, and added a duty to bury the body and sell the property to settle the deceased’s debts. Otherwise, the system wasn’t much changed.

Coroners were local elected officials, and often held other jobs like woodworker, butcher, baker, or undertaker. Since the position wasn’t based on any sort of qualifications, it was prone to influence and bribery amongst the voters and political leaders.

They didn’t have to be good at their job. They just needed to know how to play the game.

Thus began a few centuries of incompetence and corruption. Kickbacks and extortion were common. Workplace deaths could be covered up with money, and undertakers could buy business. Coroners still held inquests at their discretion, which earned themselves and their juror buddies extra cash. Instead of performing the investigation honestly, they’d go along with whatever the police or prosecutors wanted.

Physicians that worked with coroners were equally terrible. Good doctors had successful practices and couldn’t be bothered with examining bodies all night or devoting time to testifying in court.

Instead, mediocre doctors did token exams (or sometimes no exam at all) and chose arbitrary causes of death. They usually had a handful of favorites, which they’d freely slap on death certificates with no evidence to back up their findings. To be fair, medical schools didn’t provide any postmortem education. Doctors focused on treating the living.

The police weren’t any better either. Back then, many officers didn’t even have high school educations. They were hired for brute strength, not intelligence. Scientific homicide investigation was definitely out of their league. One of the most rigorous training courses in the nation during 1910 was merely eight weeks long. It was no wonder they routinely blundered through crime scenes and destroyed evidence.

The position of coroner was routinely given out as a political prize that raked in cash. There were an astonishing 43 coroners in Boston, compared to 4 in New York City (3x the population). Finally, a major scandal in Boston led lawmakers to realize the coroner system was irreparably flawed.

In 1877, a coroner held an inquest for an infant found in a trash can in his district. He paid himself $10 and each of his jurors $2. The infant’s body was then dumped in another district, and a different coroner repeated the inquest and got paid. The same baby was dumped four times before word got out and the despicable act was stopped.

That was a little lengthier than expected, but bear with me. The gist: old-timey coroners were awful, and police were inept. Things needed to change. A movement began to replace incompetent, untrained, and easily corrupted coroners with qualified medical examiners (actual doctors trained in forensic pathology).

OK, So What Does Frances Glessner Lee Have to Do with Any of This?

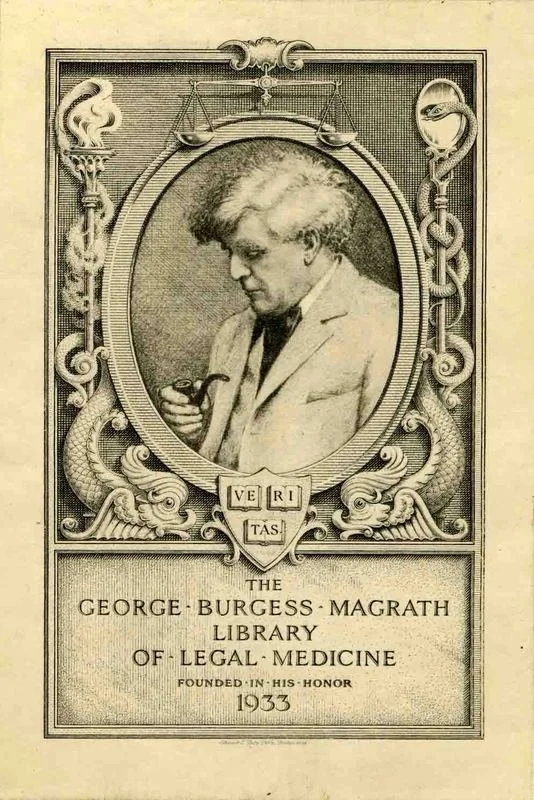

Lee maintained a close friendship with Dr George Burgess Magrath, who became one of Boston’s first medical examiners. He was exceptionally well trained in pathology and legal medicine, having spent over a year touring Europe to observe different processes.

Magrath was deeply frustrated by the laws governing medical examiners and the myriad flaws in death investigation. The office of medical examiner was still new, disorganized, and underfunded. He expressed his concerns to Lee, and her interest and appreciation of the subject exploded into action.

Lee approached the president of Harvard in 1931 and offered to pay for her friend Magrath to teach legal medicine (he’d been doing it for years for free). Lee also pledged vast sums of money to create a new department at the school: the Department of Legal Medicine. One of her conditions was that she herself would be allowed to serve as Magrath’s teaching assistant.

She also established the George Burgess Magrath Library of Legal Medicine, donating 1000 special books to the department. A health scare prompted her to write a new will giving Harvard $1 million for the department, stipulating that she would now hold the title of library curator and be granted privileges around the school.

Bit by bit, she used her wealth and influence to push her way into the very university she’d always dreamed of attending.

Lee and Magrath recognized the lack of available training in legal medicine, which prevented the switch from coroners to medical examiners. Lee wrote up a proposal for a new field of study and pulled out her checkbook again. She endowed Harvard with $250,000 (about $5 million today) with a goal of turning her new department into a factory to produce medical examiners trained in forensic pathology.

Meanwhile, she supported her old pal Magrath financially (both publicly and anonymously) so she could rely on his expertise to run her program.

A couple of years passed. Magrath’s declining health caused him to retire in 1937. The program was briefly put on hold while his replacement, Dr. Alan Richards Moritz, spent two years training in Europe.

In 1940, Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine became operational. It was slow going. Bodies were difficult to come by, and district attorneys weren’t consulting with them as expected. The local police didn’t want a bunch of college boys telling them how to do their jobs as they bungled crime scenes.

Despite the reluctance of outside agencies to cooperate, Lee barreled ahead and provided her department with the latest and best instructional tools. She purchased or commissioned photographs, lantern slides, an autopsy film, plaster head models with injuries, an exhibit on decomposition, and plaster plates painted with simulated gunshot wounds (she paid for 44 plates at $60 each, which is roughly $27,000 in today’s currency).

Aside from her work at the department, Lee also spent a considerable amount of time building a rapport with the police. She toured, observed, and questioned many police departments to improve crime scene training.

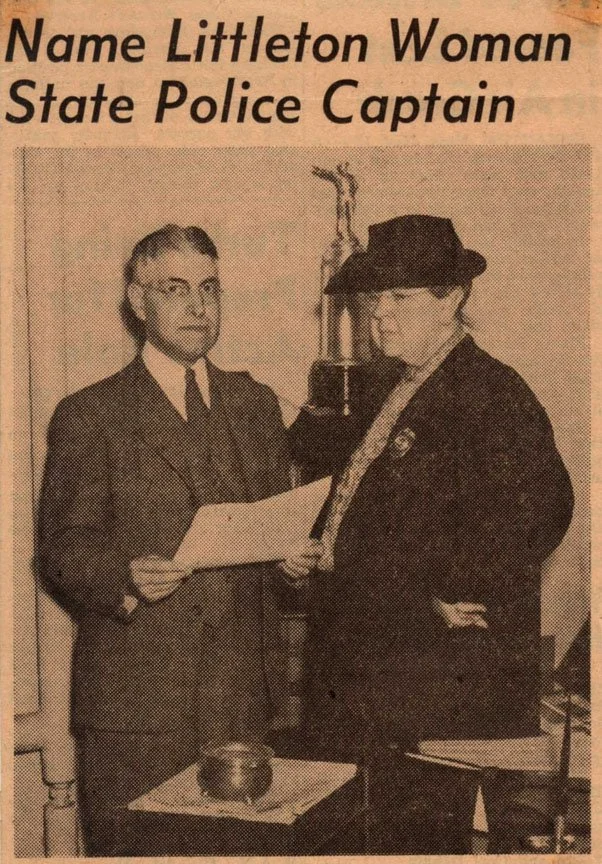

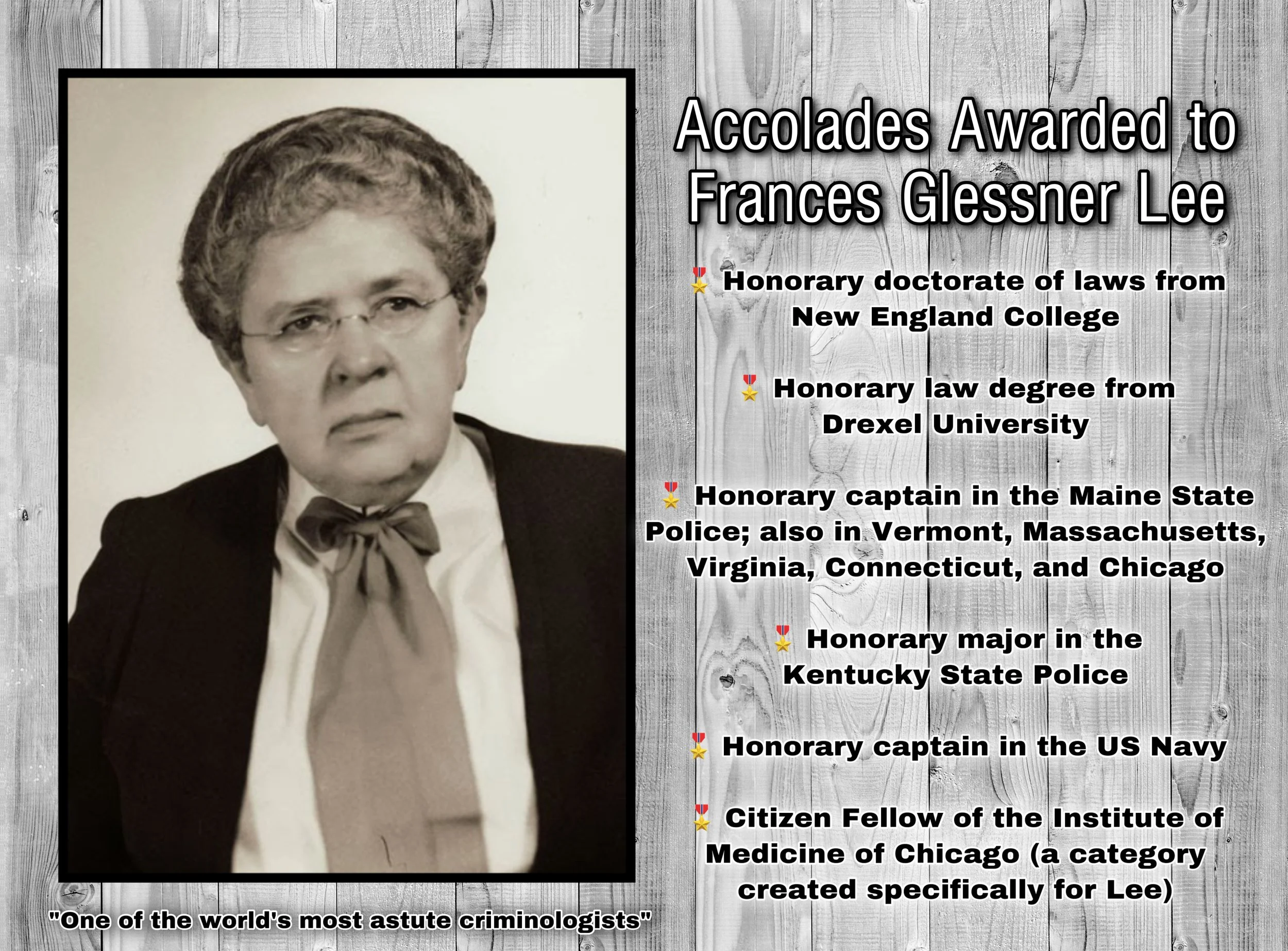

In recognition, the New Hampshire State Police named her as their director of education and commissioned her as a captain. At 66 years old, she became the first woman to hold that rank in the entire United States.

Though she never arrested anyone, the post was real rather than honorary. She carried the gold badge in her purse and identified herself as Captain Lee.

Get To The Point Already!

Alright. Captain Lee’s legacy lies in her homicide detective training seminars and infamous death scene dollhouses. Grasping the critical importance of proper crime scene investigation, she created an intensive (but not overly technical) one-week seminar for law enforcement.

Again, she manipulated Harvard into allowing their name to be used in association with her seminars. Captain Lee fully funded and engineered the seminars, but her graduates received a completion certificate showing that they’d been taught at Harvard. They deliberately made it brag-worthy for these officers with mediocre educations.

Captain Lee’s twice-yearly seminars taught the best and brightest officers how to probe unexpected and unexplained deaths properly. Curriculum included estimating time of death, decomposition and other postmortem changes, blunt and sharp force injuries, and various other subjects related to death investigation. Perhaps the most valuable skill taught was how to observe.

How do you teach someone how to observe? Captain Lee knew that viewing actual crime scenes was the best method, but impractical. Crime scenes in film and photograph lead the viewer’s eye and point out evidence. She needed a teaching method that was visual, allowed students to inspect at their own pace, and didn’t give away the answers.

Her solution: three-dimensional scale models.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death!

Fiiiinally we’re getting to the most unique part of the story (at 60% through the book, I might add).

There is a LOT to say here about Captain Lee’s extraordinary project. She used her conventional skills in the womanly arts of knitting, crafting, and painting to create the most effective homicide investigation training tool in history: doll house sized dioramas of crime scenes. Can you imagine anything more unlikely? In order to do justice to this amazing feat of art and science, I need to dedicate a new blog post entirely to the Nutshells.

“What?!” you say, “I just read this super long post for no reason?! All I wanted was to see cute murder scenes!”

Don’t worry. You can read all about the construction and exquisite details of the nutshells in my companion blog post here. I’d encourage you to finish this post first, as it describes the legacy Captain Lee left and the impact she made on forensic investigation. She deserves to be recognized for her work.

For now, here’s what you need to know about the Nutshells.

Captain Lee commissioned her carpenter to build about 20 small rooms or structures, and she decorated them to resemble average or lower middle-class homes. She used a 1”:1’ or 1:12 scale, making the dolls about 5-6” tall. Every single thing she used fit her scale, even the tiny hinges on the doors.

Some items were store bought. Most, however, had to be custom made to Captain Lee’s stringent specifications. Lee knitted tiny socks, painted bodies with discolorations, and literally spent hours rubbing worn patches into the linoleum floors. Her attention to detail was mind-boggling.

The scenes were based on composites of real criminal cases and fictional scenarios. Rather than having obvious solutions, the dioramas were intentionally ambiguous. They were not meant to be “solved.”

Instead, they taught investigators how to notice crucial pieces of evidence and how to interpret crime scene clues. It was important for them to avoid jumping to conclusions or only collect evidence that supported their hunches.

Although Captain Lee didn’t keep itemized lists of her expenditures, it’s estimated that she spent about $3000-$6000 in materials and labor to produce each Nutshell. In today’s currency, that represents a total investment of approximately $900,000-$1.8 million!

Then What Happened?

The Nutshells and the seminars were phenomenally successful. Captain Lee spent exorbitant amounts of money hosting a fine dinner at the Ritz-Carlton for each seminar group. She fussed over every detail, including seating charts, to maximize socialization amongst the 40 guests.

In this way, she ensured her attendees would bond and remain in contact with their elite new circle. The opulent meal impressed upon them how special the training was, and that they should use their knowledge wisely.

How fancy were the dinners? The floral centerpieces alone cost about $6000 (in today’s money), with the entire spectacle totaling about $25,000 per seminar. It all came from Captain Lee’s pocket, not Harvard’s.

Sample of a Ritz-Carlton banquet hall

Captain Lee’s remarkable combination of dollhouses and murder was tailormade for the media. She agreed to news articles, a pictorial in LIFE magazine, and a movie by MGM Studios (Mystery Street, 1950), as long as it focused on the science of death investigation rather than herself. Preferring to garner attention for her department and seminars, she studiously avoided the spotlight.

In an inspired move, she scored a valuable friendship with Erle Stanley Gardner, author of the bestselling Perry Mason series. After she sternly criticized his formulaic plots and portrayal of police as uneducated fools, Gardner took the knowledge he gained from attending the seminar and wrote better books. In doing so, he brought favorable publicity to legal medicine.

Gardner dedicated a book to Captain Lee, and she then arranged for a scaled down Nutshell sized copy of the first 32 pages for a dollhouse.

Though the seminars flourished, Captain Lee’s relationship with Harvard University soured. She withdrew her financial support from the department and decided not to donate her Nutshells to Harvard Medical School outright. She rewrote her will after another health scare in 1950 (age 73) and established a trust to continue the seminars in the event of her death.

Five pages of detailed instructions for the new Frances Glessner Lee Foundation board directed them how to conduct the seminars, selection and vetting of students, the exact timetable of subjects, how to line up lecturers, and the art of hosting the fancy dinners, complete with menus and seating directions.

She also warned her board to keep Harvard at arm’s length and to further her department rather than Harvard Medical School. She slammed Harvard multiple times, calling them old fogeyish, ungrateful, and stupid, as well as clever and sly. They were, after all, only letting her hang around because they expected a large inheritance.

Captain Lee had the last laugh. When she finally died in 1962 (age 83), she left an estate worth about $9.2 million (today’s currency). Most was divided between her children, but she set aside a portion for the Frances Glessner Lee Fund for the Study of Legal Medicine.

She left $0 for Harvard.

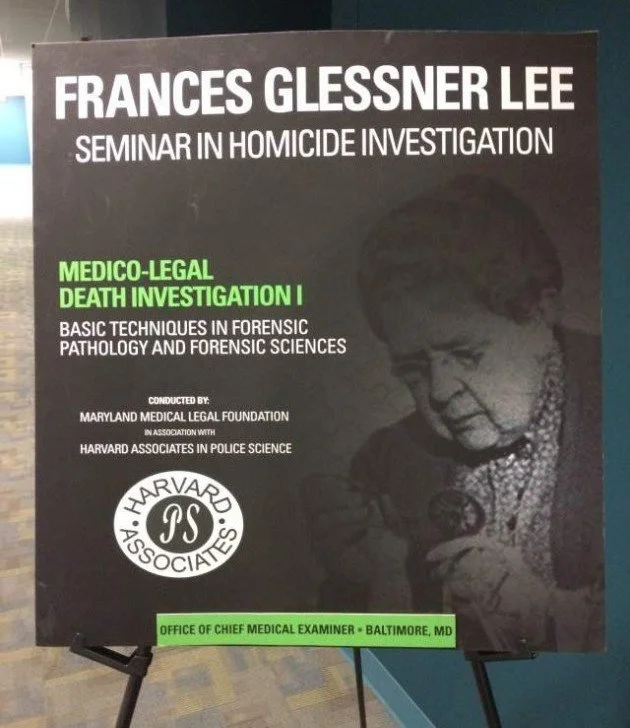

Within a few years of her death, her department closed to cut costs and was absorbed into a division of Harvard Department of Pathology. The Nutshells moved to Baltimore’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, where seminars are still held to this day. The Frances Glessner Lee Seminar in Homicide Investigation is the longest running training program of its kind.

Despite the obstacles Captain Lee faced as a woman and as someone without letters behind her name, her dogged determination pushed her to excel in an unlikely field. She used her wealth and influence to manipulate organizations and mold them to suit her goals.

She propelled the science of homicide investigation into something of vital importance and public interest, leading to one of the most popular genres of film, books, tv, podcasts, and reality shows.

Forensics are cool, because of Captain Lee!

Wow, That Was Super Long!

Sorry, I got carried away with the book dissection and ending up retelling the entire story. Oops.

Nevertheless, there are plenty more details if you’re still interested in reading the book. As I said at the beginning, it’s worth the read as long as you know what you’re getting into.

Bear in mind that it was written by a journalist, who seems better at presenting facts than at weaving a story. I found the timeline to be a bit scrambled. There was also excessive detail about people and subjects that were inconsequential to the book. Like, learning all about the architect of Captain Lee’s childhood home was probably unnecessary. Still fascinating!

Want More?

Satisfy your curiosity about Frances Glessner Lee and her amazing work by checking out these links. Also, don’t forget to see my follow up post CSI: Dollhouse, which covers every Nutshell diorama in minute detail.

Sources and Links

Amazon: 18 Tiny Deaths by Bruce Goldfarb

Video: Interview + Q&A with Bruce Goldfarb

Murder Is Her Hobby exhibition by the Smithsonian: video, images, and interactive 360 virtual tour (5 dioramas)

Family home/historical site of the Glessner Family

Video and official website for Of Dolls and Murder documentary film narrated by John Waters

Video: The dollhouses of death that changed forensic science

Photos: from the coffee table photography book by Corinne May Botz

Death in Diorama: an awesome website devoted to FGL and the Nutshells

Video: brief news feature about the Nutshells

Training: Maryland Medical Examiner

Website for Harvard Police Science seminars and alumni

Wikipedia for Frances Glessner Lee

Wikipedia for the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death

Related reading: learn more about the corruption of the coroner system in the Deep South with The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist. I highly recommend it, but be forewarned that the injustice is so appalling you’ll want to scream into the void.

Veteran funeral director, embalmer, and lifelong bookworm, Louise finally found her purpose: educating and entertaining strangers on the internet about dead bodies and funerals.

Her blog, Read In Peace, combines her passion to educate with fun and humor. She shares tips and useful information about death and funerals, along with lighthearted “dissections” of related books and movies.

Louise is currently working on her first book, a nonfiction guide called Embalming For Amateurs.