Kids & Grief: The Ultimate Directory

An extensive collection of simple explanations and resources for grieving children and their families

Help! How do I tell my child a loved one has died?

Help! How do I explain death to a child?

Help! Should my child attend the funeral?

Take a deep breath. There’s a lot to cover here and it may feel overwhelming. You will get through this, a little bit at a time.

Let’s start with some basic Do’s and Don’ts, then branch out into deeper topics. Not everything will apply to your particular situation. Key topics will be big and bold so you can easily skim past sections you don’t need at the moment. Links to relevant resources are scattered throughout, and I’ll include more at the end. For faster navigation, jump straight to:

Starting the Conversation | Bluntness & Honesty | Age vs Understanding | Myth: Be Strong | Lies & Secrets | Don’t Be Judgy | Physical Symptoms | Coping Tools | Prepare a Script | Helpers & Mentors | Attending Funerals | Religion | Suicide | Overdose | Miscarriage & Stillbirth | Mass Tragedies | School Shootings | Pet Loss | Movie Lessons | Processing By Playing | More Resources & Links | Grief Books | Say This, Not That | Teachers & Schools | Interacting With Grievers | Grief Organizations | Referenced Articles | Conclusion

Note: as of June 2022, I have added a more specific section addressing school shootings. Click here to scroll straight to it.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet.

I’m going to break down each of these into why’s and how’s. After that, I’ll cover some specific topics like:

should my child attend the funeral?

religion

suicide deaths

overdose deaths

miscarriage/stillbirth

mass tragedies

pet deaths

I have a collection of resources for further reading, which I’ll describe and link toward the end. Topics include:

grief lessons from Pixar movies and Harry Potter

lists of age appropriate books

training modules for teachers and school staff

Sesame Street’s collection of tough talks

ways to approach grieving people

database of support groups, camps, and counseling

As you can see, there’s a LOT of information to digest here. Bookmark this page and come back as needed. Your grief needs will change over time. Keep a notebook handy to write down helpful tidbits. You’re not expected to remember everything.

OMG How Do I Even Start This Awful Conversation?!

There’s no one-size-fits-all script, but start here.

Keep it simple.

Keep it honest.

Collect your own thoughts and emotions first, even if you only keep it together for a few minutes.

What you say will depend on the child’s age and level of development (we’ll get to that in a bit).

You don’t need perfect words

You don’t need to have all of the answers.

You can be nervous and uncomfortable.

You can cry.

To get the conversation going, sit your child down and say something like, “I have some very sad news. First, I am ok and you will be ok too. I want to let you know that ______ died this morning.”

After that, figure out what their level of understanding is. Ask, “Do you know what it means when someone has died?” From there, you can fill in the gaps in an age appropriate and need to know basis. I’ll explain more about that soon, but first let’s cover something of crucial importance.

Big Concepts For Tiny Humans:

Use Blunt Honest Language To Avoid Confusion!

Our instincts tell us to shelter and protect our kids, but counter intuitively, their brains need bluntness and honesty. You must be 100% literal. Kids don’t understand euphemisms!

Consider what these phrases say if you take them literally.

We had to put Fido to sleep

Ok, then wake him up!

Grandpa went to sleep forever

I go to sleep every night, what if I don’t wake up?!

Your aunt left us

Where did she go, and when is she coming back?

Your cousin is in a better place

What could be better than here with us?

He went to be with Jesus

Why can’t I go too?

She passed away

What does that even mean?!

He was sick

Wait, sometimes we get sick too, are we all dying?

He died of old age

All grownups are old, including my parents!

How many more euphemisms do you know? Kicked the bucket, resting, didn’t make it, shuffled off the mortal coil, followed the light, went home, pushing up the daisies, expired and gone to meet his maker. For a child, these statements are very confusing! They can also lead to fears of sleeping or catching a cold, fear of abandonment, feelings of rejection, and even guilt if they previously wished for a loved one to go away.

As cold as it sounds, use blunt words: He died and is not going to be alive again. His body stopped working. He isn’t suffering. He can’t feel anything. It’s not the same as sleeping.

This blunt honesty needs to be balanced out with reassurance. Remind your child that it’s OK to feel lots of emotions, and that some of it can be scary or confusing. Let them know that the death was not their fault. Be sure they understand that being sick doesn’t mean they will die if they catch a cold, and that they and your family are safe. Promise your child they’ll be taken care of.

Age vs Level of Understanding

Clearly infants, toddlers, children, tweens, and teens comprehend loss and grief in vastly different ways. Here are some general guides to how children of various ages respond to loss and some of the best ways to help (What To Expect At Different Ages tip sheets courtesy of The Dougy Center).

What about kids a little older than 0-8? They understand a lot more, but they’re still not quite miniature adults. For details about the 9-12 and 12-20 crowd, check out Childhood Grief: The Influence of Age On Understanding (they cover the younger ages too). Here’s the gist of it:

The 9-12 kids start understanding that death is final. They may be curious about the physical aspects of death. They may refrain from showing emotion, and are concerned with how others appear to grieve. Allow them to offer input and be involved in services. Watch out for disruptive behavior at school, withdrawal from friends, and changes in eating and sleeping.

12-20 year olds are capable of abstract thoughts about death and the afterlife. They may search for meaning. Avoid forcing them into a position of consoling others, like younger siblings. They may prefer to have discussions with someone other than you. Watch out for disruptive behavior at school, risk taking, and drug or alcohol use.

Note: children are not static! They grow up fast, and their brains change and evolve almost daily. A child can experience “regrief,” which is essentially reprocessing the loss through a more mature lens. They’ll likely experience new secondary losses as they understand life differently. Learn more about regrief and grief monsters here.

Myth:

“Be Strong. Don’t Cry.”

Those words can be so damaging, for both you and your kid. If you can’t cry when a loved one dies, when can you cry?! Prepare your child for a range of unexpected emotions besides sadness, such as anger, guilt, fear, resentment, and confusion. Give them permission to show emotions! Model this behavior by allowing them to see YOU expressing your emotions – in moderation.

If you need to completely fall apart, they don’t need to witness that. Kids take cues from adults. Think about your kid taking a tumble and looking to you before crying. If you jump and shout, the kid understands that their injury is a Big Deal and they’ll start wailing. If you show a milder response (“oh dear, let’s pick you up and kiss it better”), they might shed some tears but not be inconsolable.

Your calm will become their calm. Get your own big emotions out in a safe space, then express your smaller emotions with your child without over-worrying them. It’s a bit of a fine line: share your feelings so they know their feelings are acceptable, but have your own total meltdown out of their sight.

Don’t forget to give your child permission to be happy! Explain that grief sometimes comes in waves of conflicting emotions. They can feel more than one emotion at the same time (happy that it’s a special holiday, but sad that their loved one isn’t there). Visit Exploring the Mixed-Up Emotions of Grief for a couple of art activities to help them understand the concept.

Lies and Secrets

Kids aren’t stupid. They can sniff out inconsistencies and catch you in a lie. This is not a good time to risk damaging their trust in you. Be honest. That doesn’t mean you need to spill every gruesome detail about the circumstances. They’re on a need to know basis, but what they do know ought to be truthful.

Keeping secrets can backfire too. Do you want your child to wonder what you’re hiding? Make their own wild guesses? Find out from someone else? Harbor resentment from being deceived?

The unknown can be worse than the truth, so plan to share information tailored to your child’s age and understanding. It doesn’t have to be all at once. You can wait until they ask direct questions.

Don’t Be Judgy

Kids are not small adults. Their thought processes are still developing. They have weird priorities and are naturally curious. They’ll likely come up with some really bizarre thoughts about death and grief.

Respect their questions! Kids don’t know that their questions are awkward or perhaps socially inappropriate. Answer them in a calm and straightforward way. Don’t embarrass or shame them. Don’t recoil from their blunt or self-centered thoughts. Don’t get upset if they appear not to care or are very matter of fact about the death.

Allow them to express thoughts of anger and blame without reacting with your own anger. Be willing to answer the same questions over and over and over again. This helps kids clarify their understanding and be comforted by consistency.

Physical Symptoms

Your child’s grief may show up in their body as headaches or stomachaches. Sometimes it’s because they can’t put a name to their feelings. Other times it’s because their little bodies are stressed or their routine is off. See if they can make a connection between their physical symptoms and their emotions.

If they’re mimicking the symptoms suffered by their lost loved one, explain the illness and death, then reassure the child that they’re OK. If necessary, check in with their pediatrician to give them peace of mind. Expect other physical manifestations of grief, such as behavioral regressions and outbursts, bed wetting, changes in appetite and sleep.

Coping Tools

Here’s your chance to model self-care. Teach your child by example that bottling up your feelings isn’t healthy. Work together to find ways to get their “inside” feelings to the outside. Say, “When I feel sad/mad/upset, I like to _____. What helps you?”

Some kids benefit from drawing their feelings. Some want to talk. Others need physical activity. There are workbooks to help kids channel their thoughts onto paper. Even something like ripping up paper can release anger. Check out some crafty activities, like this Coping Skills Fortune-Teller. Remember those from your childhood? Now you can put it to better use than finding out if you’ll live in a mansion or marry your crush.

Teach your child to recognize when they need additional help. Kids often get extra coaching when preparing for difficult tests or competitions, and they can treat this difficult experience the same way. Asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness. It’s simply acknowledging that their experience is more challenging than usual.

Help Your Child Prepare A Script

Other people will talk to your child. They will have questions, condolences, and advice. Some of it could be helpful, but unfortunately it could also be incorrect, contradictory, or upsetting.

Give your child some words to fall back on. Tell them it’s OK to talk, but also OK to keep things private. People can be nosy about the cause of death. You can give your child simple words (his body stopped working, she died in a car crash) or they could say, “I don’t want to talk about it.”

Explain that grown-ups will inadvertently say hurtful or confusing things (God wanted her for His garden, at least you still have your dad). Give them some appropriate responses. Perhaps you and your child can tailor some words based on these 6 Polite but Effective Ways to Deal With Unwanted Advice.

Identify Helpers and Mentors

Don’t expect your child to open up only to you. Your child may want to avoid disappointing you or causing you pain. Help your child identify trusted adults they feel comfortable talking to. Maybe their teacher, coach, favorite uncle/aunt, or other mentor. They might want to try a therapist, doctor, or a support group of peers going through similar experiences.

It’s better for your child to talk to someone rather than no one.

Should My Child Attend the Funeral?

Short answer: YES!

Longer answer: every child is different (age, emotional development, and relationship to the deceased). The best thing is to fully explain what will be happening and ask if they want to go.

Kids can benefit from attending and participating in funeral rites and memorialization. Barring their attendance can lead to resentment, or fear of what must be so horrible about funerals that they must be protected. The deceased was part of their life too, and their sudden disappearance needs to be addressed. Give them an opportunity to say goodbye.

Here’s some key instructions:

Have an honest discussion first, and assess their worries and fears.

Tell them what to expect at a viewing or funeral, including descriptions of the facility, casket, and body.

Explain all of the emotions they might witness or feel.

Remind them that other adults might have awkward conversations or inadvertently say hurtful or confusing things.

Make a plan: allow your child to take breaks, and bring some quiet activities.

Help choose a grown up to stay by their side (if you are consumed with responsibilities or emotions, you won’t be able to give your child your undivided attention during the services).

Find a way to include your child if they wish. They may want to say a few words, sing a song, or draw a picture to put inside the casket.

Respect your child’s decision if they decline to participate or attend, but provide opportunities for them to change their mind.

Don’t pressure or force your child to do something they’re uncomfortable with.

For detailed step-by-step descriptions of what to expect at funerals, go here and here. This preparation is crucial!

Religion:

Helpful or Harmful?

This can be a touchy subject. Families often have different belief systems. After a death, some people lean heavily on their religion and others begin to question their faith. It’s up to you what you tell your child about Heaven, angels, reincarnation, etc. Prepare for push back or resentment if you say, “God took her” or “it is God’s will.” Consult your church for guidance. Read The Relationship Between Grief and Belief to understand that you can have faith and still grieve. Read Cultures and Grief to learn customs and beliefs. Faith can help children grieve, when approached carefully.

If you are not religious, it can be really awkward and confusing when people offer religious words of comfort. Explain to your child the things they might hear and reassure them that their loved one hasn’t been condemned to a fiery eternity. Here are a couple insights and resources for families who don’t identify as religious.

Death By Suicide

Suicide is still a stigmatized death and it creates complicated grief. Your instinct may tell you to fabricate a story for your child (heart attack, car accident), but that does them a disservice. Lying or deceiving can create trust issues and resentment when (not if) they discover the truth.

FYI, we no longer say that people committed suicide or completed/succeeded at suicide. Those phrases are loaded, and we have better alternatives. Simply say, “She died by suicide. Do you know what that means? It means that she made her body stop working.”

If your child is curious, you can explain how suicide happens (without necessarily telling them the specific method used). Compare it to an illness of the body, but one that affected their loved one’s brain. Their brain wasn’t working properly, and they chose to end their mental/physical pain by making their body stop working and not be alive anymore. Their brain was sick and may have lied to them about being better off dead. Be sure to note that it’s not the child’s fault.

You can segue into a teachable moment here. When your brain isn’t feeling right, it’s helpful to talk about it. Sharing feelings, seeing a doctor, getting therapy, and taking special medication are all ways to help your brain get better. Ask your child who they would feel comfortable talking to if they need to get some big feelings out or if their brain is having a difficult time. Without shaming or judging the deceased, make sure your child understands that suicide is not the answer.

(If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts or tendencies, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255)

If you want to delve deeper into this conversation, take a look at In Memory Robin Williams: How to Talk With Kids About Suicide. It explains more about how people can appear happy and successful, but are actually suffering inside. It also reminds us that celebrity and suicide deaths can reach our children’s ears quickly via social media.

Death By Overdose

Overdose deaths are also stigmatized and complicated. Some children are aware of a loved one’s addiction and/or erratic behavior, but others are caught entirely by surprise. There can be feelings of shame, blame, judgement, guilt, and anger. Again, reassure the child that it’s not their fault. Speak respectfully about the deceased and try not to project your own conflicting feelings about the situation. Don’t reduce a person’s life down to just their cause of death.

Create a distinction in your child’s mind about drug abuse vs medicine taken for legitimate medical purposes. Not all drugs/medicines are bad. Addiction is an invisible disease that makes a person take more than is safe, and can cause death. Listen to doctors about what medicines are safe, and follow the directions on your prescription.

Further reading: 10 Helpful Tips for Talking with Children about the Drug-Related Death of a Loved One

Miscarriage & Stillbirth

Pregnancy loss has historically been somewhat secretive. Parents are often isolated in their grief, and may wonder whether to include their living child in the knowledge of the loss. Should you tell your child? And what if the child wasn’t even aware of the pregnancy yet?

Yes. Tell your child. They’ll notice that something is wrong and that their parents seem “off.” They may worry. Even if you think your child is too young to understand, they’ll pick up on your feelings. Having a conversation about why you’re sad and what you can do about it will help set the tone for how your family handles painful emotions. Teach them to talk about feelings, not conceal them.

For more detailed tips, visit the source How To Talk To Children About Miscarriage and Stillbirth.

Mass Tragedies

The world can be a scary place sometimes. Natural disasters, school shootings, large accidents, and terrorist attacks consume our news feeds. There’s no foolproof way to shelter children from these terrible incidents, so we need to know how to explain what happened and dispel fears.

For a great guide, read Talking to Kids About Mass Tragedies and Other Events, then fall back on the words of Mr. Rogers:

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping. To this day, especially in times of ‘disaster,’ I remember my mother’s words, and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers – so many caring people in this world.”

School Shootings

As a parent of elementary school aged children, I’ve had to engage in some difficult conversations in the aftermath of the tragedy in Uvalde, Texas. I’m reluctantly adding a new section to address school shootings rather than lumping them in with mass tragedies.

How do you explain to a child that monsters intentionally invade their safe, nurturing schools intent on murdering children and beloved teachers?

If your instinct is to avoid the discussion, think again. Children talk to each other and compare notes. If they don’t find out the facts from you, they’ll cobble together who-knows-what from their friends. Here’s a few quick points then follow up links for full resources.

Keep it simple. Don’t overshare. Assess what they already know, then fill in gaps as necessary. Offer reassurance (as in: you are safe, this incident happened far away and the bad person is no longer a threat).

Explain that school shootings are rare. It really, REALLY doesn’t seem that way at the moment, but you can explain the crucial difference between the possibility of a shooting vs the probability of a shooting.

Limit your child’s exposure to news coverage. This impacts their perception on how often shootings happen. News media is notorious for sensationalizing events, and children may be overwhelmed. Monitor your own discussions when you know your child is listening.

Remind them that active shooter drills are not done with the expectation that a shooting is eventual. We practice going through the motions of emergencies so everyone is familiar with how things work. Fires and earthquakes are also rare, but we prepare just in case. We don’t want extra confusion and panic if it can be avoided.

Talk. Bring up emotions, how to express them, how to ask for help, how to tell an adult something is worrying them. Watch for changes in behavior. Short conversations are ok, and answering the same questions again and again is ok. Tell them that all kinds of emotions are normal, whether they feel like crying, or if they’re scared or angry.

Regular fear is ok, while paralyzing, incapacitating fear is not. Chances are, however, that you will be more worried about a school shooting than your child. They have an egocentric mindset that protects them from experiencing anxiety on the same level as adults. This begins to change as the child develops into a teenager.

For older children, they might feel better if they turn their anxiety into action. Activism against gun violence can channel their energy and reduce feelings of helplessness.

Additional links about discussing school shootings:

“Talking to Children About Violence: Tips for Parents and Teachers” - National Association of School Psychologists

“How to Talk to Kids About School Shootings” - Child Mind Institute

“What to say to kids about school shootings to ease their stress” - NPR

“An Age-by-Age Guide to Talking to Children About Mass Shootings” - NY Times

“Talking to Children About the Shooting” - The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

“Talking to children about terrorist attacks and school and community shootings in the news” - National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement

“Gun violence, grief, and trauma: A resource guide for students, teachers, and parents” - Chalkbeat

Pet Loss

Children are attached to their pets in special ways. They’re often more connected to the animal than they are to other family members. The loss of such a treasured companion can be more devastating to a child than a human death, but it also provides a valuable opportunity to introduce concepts of loss and grief at an early age. Compare that to someone who hasn’t experienced or processed a death until they’re in their 20’s-30’s. The death of a pet can teach a child important lessons for the future and prepare them to grieve bigger losses.

Here’s a short tip sheet and a longer tip sheet for helping kids deal with pet loss.

This article is useful too. It highlights the importance of properly explaining euthanasia (“the veterinarians have done everything that they can, your pet would never get better, this is the kindest way to take the pet's pain away, the pet will die peacefully without feeling hurt or scared”). It reminds us to NOT use the standard terminology of putting the animal “to sleep,” nor to deceive the child by saying the pet ran away or is living with a new family.

It’s important to recognize the impact pets have on our lives and to acknowledge our tremendous emotions when they die.

Teachable Moments of Death From Popular Movies

Movies can be an excellent tool for introducing difficult concepts to children. Death in Disney Movies: Making the Most of Teachable Movie Moments talks about Frozen, Bambi, The Lion King, and Up. You can expand these lessons to other movies, like Frozen II, Finding Nemo, Big Hero 6, Soul, Onward, and Coco.

The aforementioned article suggests that you watch the movie with your child, observe how they respond, ask questions to assess their understanding, and fill in the blanks using clear, honest language. Then, discuss how the characters feel. Make connections with your child’s own feelings and comparable experiences. Point out differences.

Inside Out Offers Important Lessons for Grieving Children and Adults. It teaches us that we have different, named emotions. We learn that sad is not bad, and that happy memories can be tinged with sadness. Inside Out is a great movie for illustrating how emotions influence behavior.

Harry Potter is another great source of teachable grief moments. 12 Things Harry Potter Taught Me About Loss is well worth reading in it’s entirety. To summarize, it includes:

kids grieve even when they don’t remember or never met their lost loved one

relationships continue after death

grief can make special things feel empty or meaningless

sometimes your family is not the best source for support

you can grieve for someone still alive

people who have experienced devastating losses often see the world differently

life isn’t fair; anyone can die

learning hard truths about lost loved ones is difficult

depression is soul sucking and hard to explain

the people we love are always with us, and that gives us strength

Processing Grief Through Play

How Children Process Grief and Loss Through Play tells us that when kids are exposed to painful or scary ideas, their play will reflect their efforts to make sense of what they see and hear. For example, kindergartners close to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing repeatedly knocked over block towers and laid down, playing dead. They told their teachers that they were killed by terrorists.

Naturally, this is shocking and alarming for adults to witness. It’s OK though! Play allows kids to approach scary topics in a controlled environment, allowing them to process fear, anxiety, and loss. Provide your child with generic toys or objects so they can project their imaginations onto them.

Monitor the play for signs of obsessive or repetitive behavior. Gently coax their narrative in a new constructive direction (in the case of the children and the bombing, their teacher shifted their focus from death and destruction to care and healing: they built a “hospital” and were given stethoscopes, masks, and bandages. Read the original article for more details.

Additional Resources & Links

We just covered a ton of information, but there’s still plenty more out there. Here are some extra links to the best resources I’ve found. I’ll also include the links from above so you have everything all in one spot.

Books On Grief

There are tons of children’s books about grief but they’re not one size fits all. Try to look for books in your child’s age range, then read reviews to see if they’re a good match for you. Some books have a focus on religion, different types of loss, or specific relationships. Activity workbooks are great for kids too.

Here are a few book lists to check out:

The Dougy Center

The Dougy Center is a comprehensive website for grieving kids and their families. Their resources and toolkits span all ages and relationships. Visit and explore to find:

Amazing tip sheets, activities, and podcasts

Parent, caregiver, and teacher resources

Worldwide support group locator

An extensive library of resources that can be filtered by topic, type of death, relationship to the person who died, media type, and age/type of audience. A+++, highly recommended!

Duelo Apoyo, Recursos, y Grupos para usted y sus hijos en duelo

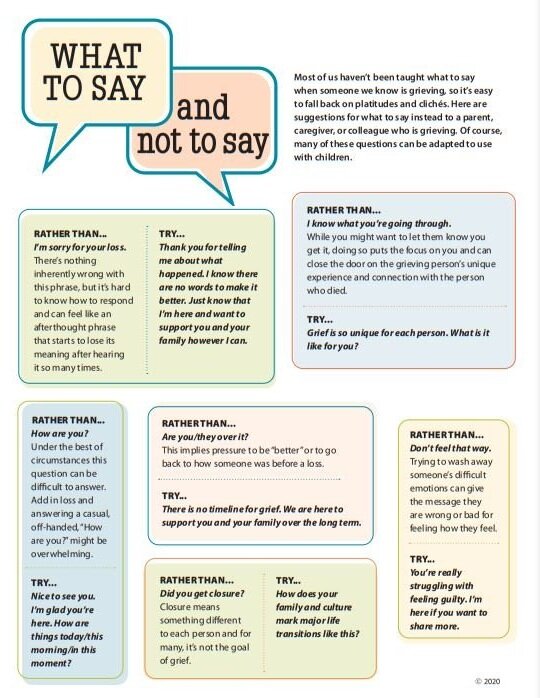

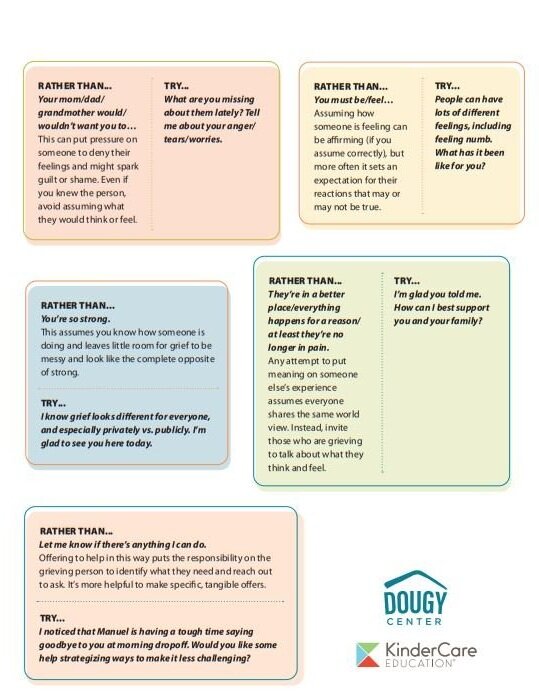

Say THIS, Not THAT

For Teachers and Schools

The Coalition to Support Grieving Students provides:

Specific grief information for teachers, principals, admins

FREE grief training modules for school staff

FREE brochures/booklets (available in Spanish too!)

Professional preparation and self-care

Crisis and special circumstances support

How to support children with intellectual and neurodevelopmental disabilities

DOES YOUR SCHOOL NEED ADVICE NOW?

Contact us at 877-53-NCSCB (877-536-2722) or info@grievingstudents.org

Sesame Street has a lovely collection of grief videos, articles, and printables here. Their main topics page has other helpful resources for Difficult Times & Tough Talks, including:

Divorce

Incarceration

Homelessness

Foster Care

Handling Emergencies

Parental Addiction

Racial Justice

Trauma and Violence

64 Ways To Meet Grieving People Where They’re At

64 tips for interacting with grieving people, such as:

Know that what a person thinks and feels in grief isn’t always rational – and that’s okay.

Try not to imagine how you would think, feel, or act if you were them. In reality, you have no idea how you would think, feel, or act – even if you’ve experienced loss yourself.

Be as supportive on day 365 or 500 as you were on day 1.

Don’t expect them to be the same person they were before their loss.

Miscellaneous Links

What’s Your Grief - Grief support for the rest of us. You don’t have to grieve alone. What’s Your Grief is a place for sharing, support, resources, & more.

National Alliance for Children's Grief - a nonprofit organization that raises awareness about the needs of children and teens who are grieving a death and provides education and resources for anyone who supports them. Find Support Groups and Camps in your area.

Guide to Grieving Support Resources - Over 40 of the best grief-related resources on the Web for children, parents, spouses, siblings, friends, acquaintances, coworkers and employers that are categorized into sections that make it easy to find what you – or someone else – needs.

Center for Loss & Life Transition - Led by death educator and grief counselor Dr. Alan Wolfelt, we are an organization dedicated to helping people who are grieving and those who care for them.

Guidelines for Helping Grieving Children - VITAS Healthcare

Referenced Articles

These articles were linked throughout my main post above, but here they are again for your convenience.

Talking to Kids About Death and Grief: 10 Comprehensive Tips

Exploring the Mixed-Up Emotions of Grief: Art Activities for Kids

In Memory Robin Williams: How to Talk With Kids About Suicide

10 Helpful Tips for Talking with Children about the Drug-Related Death of a Loved One

Helping Children Cope with the Serious Illness or Death of a Companion Animal

Death in Disney Movies: Making the Most of Teachable Movie Moments

Inside Out Offers Important Lessons for Grieving Children and Adults

Conclusion

There’s no easy way to talk to children about death, but hopefully now you have the tools you need.

If you have any questions or experiences to share, leave a comment below!

Veteran funeral director, embalmer, and lifelong bookworm, Louise finally found her purpose: educating and entertaining strangers on the internet about dead bodies and funerals.

Her blog, Read In Peace, combines her passion to educate with fun and humor. She shares tips and useful information about death and funerals, along with lighthearted “dissections” of related books and movies.

Louise is currently working on her first book, a nonfiction guide called Embalming For Amateurs.